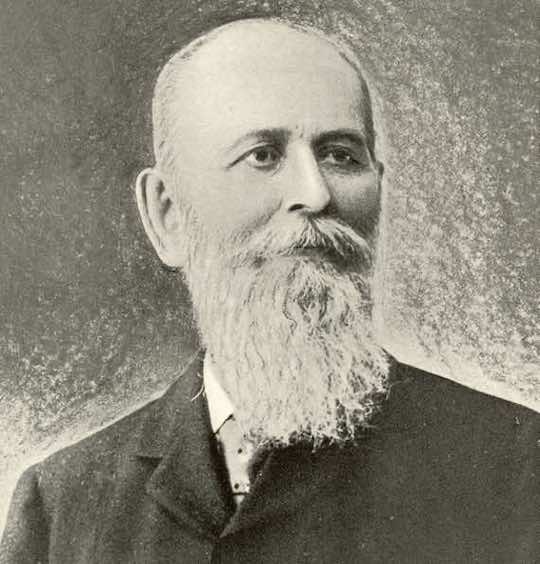

Michael (Anagnostopoulos) Anagnos

Michael Anagnos

"The name of Michael Anagnos belongs to Greece, the fame of him belongs to the United States, but his service belongs to humanity."

With these words, Governor Guild of Massachusetts, described the loss to humanity at the death of Michael Anagnos, Greek immigrant, who died in 1906.

Michael Anagnos was born Michael Anagnostopoulos on November 7, 1837 in the village of Papingo in Epirus, Greece. At a young age Michael started out as a sheep herder for his father. He then decided to go to the Zozimaea School in Janina and later graduated from the University of Athens. In addition to Philosophy, Michael Anagnos also stufdied law even thought he never practiced law. He became chief editor of the Athenian newspaper "Ethnofylax." He was imprisoned for opposing King Otho and his government's failure to give the Greek people their rights.

In 1867, while Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe was in Greece distributing relief items in Crete, Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe hired Anagnos as his secretary and assistant for the relief effort. In lieu of a salary, Anagnos requested Dr. Howe to take him to the United States. Dr. Howe willingly complied. When they returned to Boston, Dr. Howe made Michael Anagnos teacher of Greek and Latin at the the Perkins Institute for the Blind. He was also the private tutor for Dr. Howe's family. Dr. Howe had founded the Perkins Institute for the Blind in 1829.

Gradually, Michael Anagnos took over Dr Howe's responsibilities at the Perkins Institute. Anagnos devoted 30 years of his life to the improvement of the institute and its mission. One of his first and most notable accomplishments was the raising of one hundred thousand dollars for books for the blind and for the establishment of a printing plant for embossed and braille books. He founded the first kindergarten for blind children which was located outside of Boston in Jamaica Plains. His work for the deaf-blind garnered worldwide acclaim, notably for his work with Helen Keller, Thomas Stringer and Elizabeth Robin.

In 1870, Michael Anagnos married Julia Romana Howe, daughter of Samuel Gridley and Julia Ward Howe. They were married until Julia's death in 1886.

Although he became a United States, Mr. Anagnos had an affinity to his native Greece and made generous gifts towards Greek education . He made one gift of $25,000 five thousand dollars toward the support of schools in Papingo. He also supported and promoted the interests of his fellow Greek immigrants in the United States. He was president of the Boston Community of Greeks as well as the founder and president of the National Union of Greeks, the predecessor to the present Pan-Hellenic Union.

In 1906, Michael Anagnos went to Europe as he had frequently done. He visited Athens and was present at the Olympics. He then traveled through Turkey, Serbia and Romania. In Romania, he succumb to a long-standing disease and passed away on June 20, 1906. Michael Anagnos is buried in his native village of Papingo in Epirus.

Memoir of Michael Anagnos

The following is taken from the 155 page "Memoir of Anagnos" which was published in 1907, the year after his death, by the Perkins Institution and Massachusetts School for the Blind, which institutions Michael Anagnos served and directed so well and devotedly:

Michael Anagnostopoulos, or as he became known to Americans, Michael Anagnos, was born November 7, 1837, in a mountain village of Epirus, called Papingo. His father was a hard-working peasant, who had lived under the bloody Ali Pasha.

True Greek, the boy longed and labored for an education. He began in the little village school and used to pore over his lessons as he tended his father's flocks on the mountain side, or in the evening by the light of a pine torch. As he grew older, to support himself he also taught in his spare hours. His teacher advised him to go to Janina and try for a scholarship in the Zozimaea School. Passing among the first, he was aided by the great teacher Anastasios Sakellarion. As he was too poor to buy text books he used to copy them out by hand. At last his gymnasium course was worked through, and he achieved his longing by entering the University of Athens. Of the struggles at the university writes his Boston sister-in-law, Mrs. Florence Howe Hall,

'I have heard him tell the story of four students who lived together at Athens and possessed only one good coat among them, so that they were obliged to take turns in going out. I have always suspected that he was one of the devoted quartette.'

”He worked his way by teaching languages and reading proof. He took his B.A. in philology, and also studied law.

In 1861, Anagnos joined the staff of the Ethnophylax (National Guard), the first daily paper of Athens, writing criticisms and translations and then political essays, and was shortly made editor-in-chief at the age of 24. This paper was started to advocate popular rights against the oppressive government of King Otho. Our youthful hero was one of the most active in this opposition, even going so far as to be instrumental in introducing, through General Garibaldi and one of his sons, lodges of Free Masonry by the Scottish Rite as an element in the coming dethronement of the Bavarian monarch. Twice he was put into prison. His ardent share in the bloodless revolution of 1862 Anagnos in his later years spoke of with regret. At the beginning of the Cretan Revolution in 1866 Anagnos enlisted his pen in the cause of the devoted island; but his fellow editors of the Ethnophylax disagreed with him, and he resigned.

Then it was that our great American, Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe, whom as yet Anagnos knew only by his former fame as a Philhellene, came to Greece to help the Cretans, and desiring to find a Greek secretary who should act with him in the work of the relief, was directed to the young ex-editor. He at once engaged him and left him part of the time in charge of the committee's affairs, while he himself visited schools, prisons, and hospitals in Europe.

When Dr. Howe returned to Boston, he persuaded his Athenian secretary to accompany him and continue in the work of the Cretan Committee in New England. Finding him well qualified to teach, Dr. Howe gave him the task of teaching Latin and Greek in the Perkins Institution to the few blind pupils who in 1868 had pursued their studies that far; and also made him private tutor of his family. A year or two later he promoted his tutor's wish to become Greek professor in some western American college, writing in a letter of recommendation, 'He is capable of filling the post in any of our universities with honor.'

Yet so had the young Greek won the affections of the Howe family that when the time for separation had come Dr. Howe could not part with him, but placed him in a permanent position in the Perkins Institution, and late in 1870 gave him the hand of his daughter, Julia Romana. She, worthy scion of Samuel Gridley and Julia Ward Howe, was 'a woman of ideally beautiful character and deeply interested in her father's work for the blind.' For 15 years they spent a happy, though childless life together, till she died in 1886. The last words of Mrs. Anagnos were: ‘Take care of the little blind children.'

After 1870, the increasing years and infirmity of the great founder of the Perkins Institution for the Blind made it necessary that Mr. Anagnos be placed more and more in general charge of affairs, and so he became intimately familiar with every part of the establishment and its methods and ideals. Thus when Dr. Howe died in 1876, he was the only candidate seriously considered as his successor, ‘although,' says Mr. Sanborn, 'there was some question in the minds of some trustees how a native of Turkey and a subject of the Kingdom of Greece would succeed in the whole management of a Bostonian institution so peculiarly dependent on the liberality of the good people of Massachusetts, and particularly of Boston. The result of his administration (which lasted 30 years) soon solved that question. Every branch of the administration had already begun to feel the youthful energy and mature wisdom of the new director.

Writes the acting director in his report after Anagnos' death:

Trained by intimate relations with the great father of the work in this country, Dr. Howe, Mr. Anagnos saw clearly that the methods and principles used by Dr. Howe were in the main correct, and with that complete lack of conceit and entire absence of any sense of his own importance, as great as it was rare and as rare as it was beautiful, he set himself to the task of carrying out the great work his predecessor had left uncompleted, and for three decades has labored faithfully and brought this great work to a state of efficiency that is known and admired on both sides of the Atlantic.

One of his first acts was the promotion of a fund of $100,000 for books for the blind; six years later every public library in Massachusetts had been furnished with these books. Seconded by his devoted wife, he founded the kindergarten in Jamaica Plain for little blind children under nine. This beautiful work is his especial monument. Soon another $100,000 endowment was raised, and for many years he was weighed with the handling each year of over half a million dollars. He gave special attention and study to the perfection of the physical training department and to the training of the blind in self-supporting trades and occupations.

In none of the deeds of his life did that tenderness of heart and empathy for his fellow men that were ever the chief motive forces of his character, appear more conspicuously than in his work for the deaf-blind -- a work small in numbers, but in proportion to the completeness of the emancipation, tremendous in achievement. He had become familiar with the famous education by Dr. Howe of Laura Bridgman, Oliver Caswell and others, and in carrying on a like work he attracted the attention of the world in some respects even more than did the cases of his predecessors. The fame of his success in the cases of Helen Keller, Thomas Stringer, Elizabeth Robin, and others of the blind-deaf has gone round the world. I cannot refrain from retelling the story of one case (the others are equally miraculous) in the words of Mr. Sanborn:

About sixteen years ago in a hospital in the city of Pittsburgh, a pitiful case was brought to light. A little boy, deaf and blind, was sent there for treatment. His parents were too poor to pay for his maintenance in any institution, and a number of appeals were sent to institutions and individuals in his behalf, but without avail. Finally the case was brought to the attention of Mr. Anagnos. In the helpless, almost inanimate little lump of clay that was brought to his doors, he saw the likeness of a human soul, and immediately took measures to bring about its development and unfolding. So the little stranger entered the Kindergarten for the Blind in 1891; a special teacher was provided for him; and the education of Thomas Stringer had begun.

'The sightless, voiceless, seemingly hopeless little waif of 1891 has now developed into the intelligent, sturdy, fine appearing young man of 1906, who, in his benefactor's own words, 'is strong and hale, and who thinks acutely, reasons rationally, judges accurately, acts promptly, and works diligently. He loves truth and uprightness and loathes mendacity and deceitfulness. He appears to be absolutely unselfish and is very grateful to his benefactors. His is a loyal and self-poised soul-affectionate, tender, and brave. He enjoys the tranquillity of innocence and the blessings of the pure in heart. He is honorable, faithful, straightforward, and trustworthy in all his relations. He is not only happy and contented with his environment, but seems to dwell perpetually in the sunlight of entire confidence in the probity and kindness of his fellow men.'

The above is a just picture of the results thus far attained in the case of Thomas Stringer, and in the closing sentence the writer unwittingly gave utterance to his own highest praise, for if this deaf-blind boy 'dwells continually in the sunlight of entire confidence in the probity and kindness of his fellow men' it is because he has known naught but perfect probity and absolute kindness on the part of the man who, amid the multifarious cares involved in the conduct of a great institution, yet found time to take this stricken waif into his heart and love him! -- who found time to be father, guardian, and friend! -- and year after year, by voice and pen to plead his cause with a generous public, and so provide for the child's future security when his guardian should have passed from the scene.

Here is the testimony of one blind graduate, Lydia Y. Hayes, on learning of Anagnos' death:

'… I have always wished for literary ability, but never so much as now, when I desire to express what Mr. Anagnos has been to one graduate of the school. Then multiply that by every life which his life has touched, and you have the result of his influence in the world. His strength comforted our weakness, his firmness overcame our wavering ideas, his power smoothed away our obstacles, his noble unselfishness put to shame our petty differences of opinion, and his untiring devotion led us to do our little as well as we could … Better than all, he taught us to be men and women in our own homes and to the best of our ability.'

And here is how his subordinates regarded him -- from the report of the acting director:

'The relation of Mr. Anagnos to his associates was in itself a beautiful thing. He asked for no comforts of living that his associates did not enjoy. He demanded of his helpers no greater length of hours or hardships of service than he took upon himself. Each morning he met his teachers at chapel and gave every one a hearty greeting and a cheery smile that lighted up their path throughout the day.

'He would never have any praise for himself, but how often in these pages and by spoken word has he shown his appreciation of their efforts, and assigned them all the credit for the work done here. And this was genuine! It rang true! And his helpers for the most part did their best, out of interest in their work and the loyalty that he inspired.'

One of the last reports of this great educator of the blind closes with the following words:

'Encouraged by the achievements of the past, we take up hopefully the duties of another year, firmly resolved to carry forward this beneficent enterprise until we reach the shining goal at which we aim, namely, the illumination by education of the mind and life of every child whose eyes are closed to the light of day. We are aware that the path of progress which we have chosen to pursue is full of difficulties; but let us keep our faces always towards the sunshine, and the shadows will fall behind us.'

Several times Anagnos visited Europe to travel about and study the institutions for the defective, and to visit his relatives in enslaved Greece and investigate the educational possibilities of its oppressed compatriots. He was present in Paris in 1900 at the International Congress of Teachers and Friends of the Blind in the double capacity of representing his own institution and also commissioned to represent the United States government.

Though he finally became a citizen of his adopted country, yet, just as every other Greek settled in a foreign country, so Anagnos remained to the end intensely interested in the progress of his native land, and made various generous donations to the cause of Greek education, and left a life bequest in his will. The epilogue of one donation of $25,000 deposited in the National Bank of Athens towards the support of schools in his native Papingo reads:

'Having lived for many years in foreign countries, neither in sorrow nor in happiness have I ever forgotten my dear country, but have always, always encouraged her in her progress and toward her happiness. My savings, earned after many years of hard work, l throw on her soil with great joy, in order that it may produce, as l hope, the very best flowers of Greek education and development, which means the civilization of this small corner of Epirus where l first saw the light of day and into whose soul I wish to pour light.'

Moreover, Anagnos did his utmost for the cause of his immigrant brethren in America. He moved freely among the Greeks of the Boston community, frequenting their restaurants and coffee houses, helping many a recent immigrant to get a foothold, contributing freely to the Greek Church in Boston and elsewhere, officiating as chief speaker at the celebration of the Greek Day of Independence. At one time he was the president of the Boston community, and as we mentioned before, he was the founder and president of the National Union of Greeks in the United States, which society, though defunct after his death, was the fore-runner of the Pan-Hellenic Union.

In 1906, Anagnos sailed for Europe, and after visiting Athens, of whose progress he wrote enthusiastically, and being present at the Olympic Games, he traveled leisurely through Turkey where he was saddened by the oppression of his people and his course was followed by Turkish spies. He proceeded through Serbia and Romania. There a disease of long standing returned upon him. He underwent an operation, and died under the surgeon's hands at Turn Severin, a frontier town of Romania, June 29th, 1906. His body was taken to his natal village in Epirus and buried there.

”Roses white and red, with lilies and pale immortelles, clustered lovingly yesterday around the portrait of Michael Anagnos as it stood, taper-lit, in the chancel of the Greek Church at the corner of Kneeland and Tvler Streets"; so writes the Boston Herald of July 16th, 1906. "Two hours were there given by the Greek colony of Boston to the memory of their revered compatriot, and for a considerable portion of that time his praises were spoken in the language which he loved so well. The interior of the church had been heavily draped for the occasion. The symbols of woe were almost forgotten in the presence of many floral offerings, which included wreaths from the Greek Union (Helleniki Kinotis) of which the deceased was president, the St. Peter's Club (Agios Petros), the Ladies' Greek Society, and the Vassara Union."

On October 24, 1906, in Tremont Temple, Boston, exercises in memory of the great Greek, were held before a most notable gathering. General Francis Henry Appleton presided. The Rev. Paul Revere Frothingham opened with a prayer; the blind school orchestra played, a choir of blind girls sang a hymn; Mrs. Julia Ward Howe read a poem; and addresses were made by Governor Guild, Mayor Fitzgerald, Mr. Franklin B. Sanborn, Professor J. Irving Manatt, and Bishop Lawrence, and the benediction was given by the Greek priest of Boston, Fr. Nestor Souslides. Here are a few words spoken:

MR. SANBORN:

"I, who have seen many establishments directed by able chiefs, at the head of many subordinates, have never seen one where loyalty to the chief was more marked or longer continued. He held for a whole generation a place in which he was greatly trusted, in which he accomplished grand results, and in which he was true to every trust reposed in him ... and he silently fulfilled the obligation where many Greeks and many Americans would have spoken in their own justification."

GOVERNOR GUILD:

"Whatever he did was done well. It was my high privilege to know him both officially and as a personal friend, to visit and see him in his touching work among the little children, to note the kind word of cheer, the ever ready flow of kindly wit and humor, the encouragement, the almost divine patience with which the little hands were guided till those that sat in darkness gradually began to see at last a great mental light ... The name of Michael Anagnos belongs to Greece; the fame of him belongs to the United States; but his service belongs to humanity!"

PROFESSOR MANATT:

"The memory of Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe binds old Greece to young America; may the memory of Michael Anagnos be a strong bond of sympathy between his sightless pupils here and his young compatriots who sit in deeper darkness over there ... It was a unique career of this Greek among barbarians. Greeks have gone round the world and in every commercial center you will find great Greek merchants and bankers; now and then a Greek scholar like Sophocles at Harvard or a man of letters like Bikelas in France; but where, in the whole history of Greece, will you find another Greek who in a foreign land has achieved a career in the service of humanity comparable to the career of Anagnos in America? And what rarer reciprocity of service ever bound two lands together! While we recall ancient worthies, let us not forget this pair of Plutarch's men, Howe and Anagnos, who have dwelt among us in the flesh."

Greek Link With Perkins Institute

Greek Link With Perkins Institute

Dr. Howe Brought Future Director From Land of Hellenes to Boston

Few would dream there was any connection between Samuel Gridley Howe's foresaking a more profitable career and going to help the Greeks fight for their freedom and the subsequent development of Boston's Perkins Institute for the Blind to one of the greatest establishments of its kind in all the world. There was the strongest link, for on Howe's return home he brought Michael Anagnos, a youthful Greek who was in time to become Howe's secretary, then his son-in-law and finally his dynamic successor as secretary and director of the asylum, then in South Boston. A few years later Col. Thomas Handasyd Perkins, an ancestor of the late Thomas Nelson Perkins, gave his home on Pearl Street, for the institute's use. It flourished so swiltly that a hotel atop the South Boston Hill was eventually bought and con verted to house it.

Anagnos' name is a sainted one among the sightless everywhere to day, because of the devoted and ingenious quality of his labors for this pioneering humane institution. The enterprise was Incorporated In 1829, and Howe, two years later, was conducting the original classes in his father's house on old Pleasant Street, South End (now Broadway).

Succeeding to the directorship upon Howe's death in 1906, Anagnos' first step was to raise public subscriptions for publishing embossed books in the Braille style. Then he obtained for a museum stuffed objects and birds and animal specimens for object teaching. He gathered a special reference library on blindness and the blind. He started a kindergarten for blind children, accounted the first, largest and best appointed in this country if not in the world. Within 20 years he raised $1,000,000 for this unit. He established eymnastic and sloyd classes.

Along with the multiple tasks of originating and developing all these phases of the work, Anagnos found time to write voluminous but cogent annual reports of the institution's affairs, a great stimulus to the expansion of such enterprises everywhere.

It was said of Anagnos that his devotion to Greece and her national welfare constituted a real religion. Greek-blooded folk in this country chose him as president of their Pan-Hellenic Union. At his death Anagnos was mourned as "a deep thinker, a wise counselor, a prophet of god, a great hearted lover of mankind, a true and farseeing leader of the blind along the higher paths."

Born In a mountain village of Epirus, of peasant stock, Anagnos was in boyhood a goat tender. Always studious, he gained a scholarship at the University of Athens. Keenly aware of the difficulties in the paths of Greek youths like himself who thirsted for education, Anagnos early resolved that he would do what he could to lessen some of these.

Anagnos' salary as director of the institution never exceeded $60 a week. A Boston banker who knew of his dream gave him wise invest ment counsel, and at his death Anag nos bequeathed the sum of $350,000 for the founding of a free school for boys in Epirus, named for this Greek who became an American here in Boston.

Source: Collins, Edwin F. "Greek Link With Perkins Institute" The Boston Globe, 6 December 6 1940, p. 9

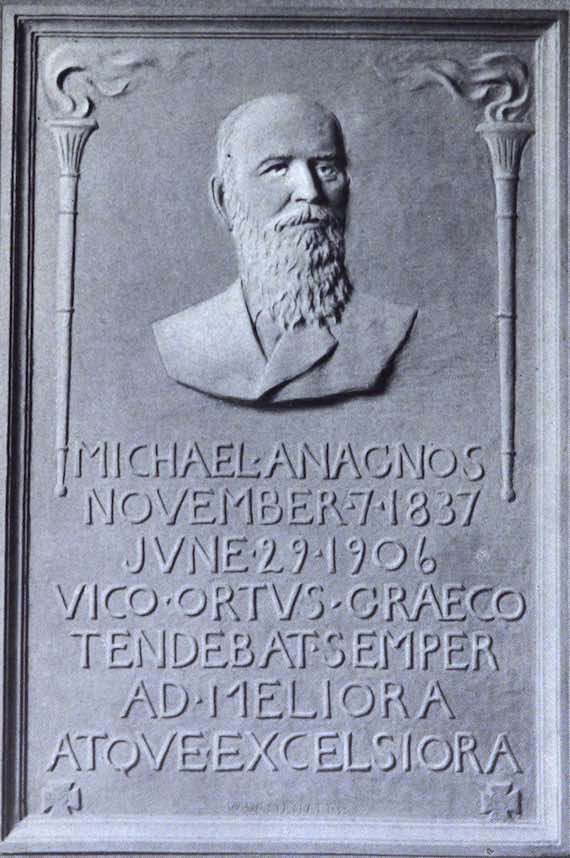

Tablet in Memory of Michael Anagnos at the Perkins Institute

Source: The Boston Globe (May 23, 1907)

Also:

Photographs, texts, and artifacts including an embossed book, a publication with pressed flowers, a musical score, tactile portrait medallions, and many portraits of Michael Anagnos with slight variations.

Small leather bound photograph album in the collection of former Perkins School for the Blind director Michael Anagnos, who served from 1876-1906. The album contains portraits of Perkins' teachers, students, and staff, in addition to teachers and students from other schools for the blind including the Royal Normal School for the Blind in England. The images are from the 1860s and 1870s.