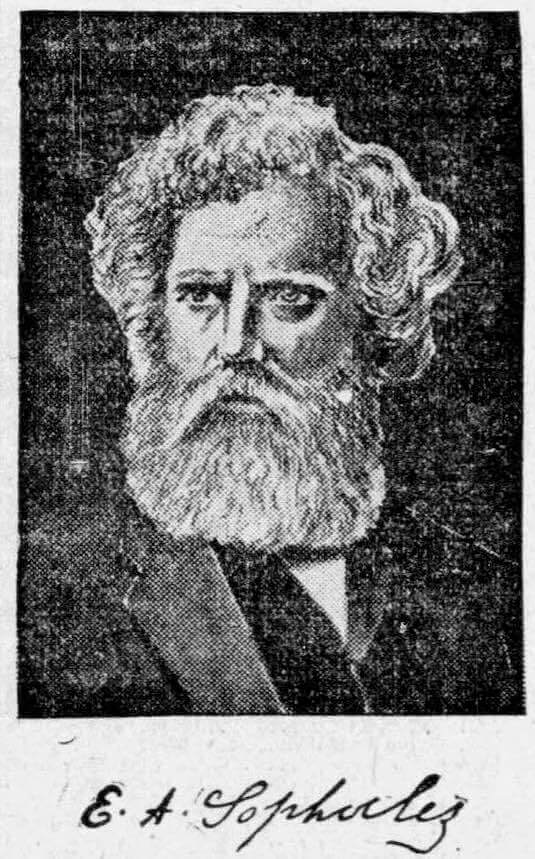

Evangelinos Apostolides Sophocles

Source: Harvard Square Library

Another renowned educator of the 19th century was Professor Evangelinos Apostolides Sophocles (1804 - 1883), born in Greece, who came to the United States in 1828, at 24 years of age. He distinguished himself as professor at Harvard University for 41 years. Professor Evangelinos Apostolides Sophocles would go on to make the greatest contributions to modern Greek studies at Harvard University and in the United States. When he died in 1883, he left his personal library and his entire estate to Harvard University.

"Under the aegis of Evangelinos Sophocles, Harvard became a world center for the study of modern Greek. Professor Sophocles not only wrote the first modern Greek grammar and first modern Greek lexicon but also a Byzantine dictionary."

– John Brademas, 1987. ("A World No Longer Narrow: Bringing Greece to American Universities")

The following biography is taken from the records of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences:

"Professor Evangelinos Apostolides Sophocles, LL.D. was born in 1804 in the village of Tsangarada in Thessaly on the slope of Mount Pelion. His father's name was Apostolos, and thus he obtained the patronymic Apostolides. The name of Sophocles, by which he has always been known away from home, was given him in his youth by his teacher Gazes as a compliment to his scholarship. He spent his childhood in his Thessalian home. While still a boy he accompanied his uncle to Cairo, where he spent several years in the branch of the Sinaitic monastery of St. Catherine (of which his uncle was Hegumen) visiting also the principal monastery on Mt. Sinai itself. He returned to Thessaly in 1820, where he remained a year at school, chiefly studying Greek classic authors, under the instruction of several teachers of repute, especially Anthimos Gazes, who had been 25 years in Vienna. The breaking out of the Greek Revolution in 1821 closed this school, and Sophocles returned to the monastery of Cairo.

”After a few years he left the Sinaitic brotherhood on the death of his uncle, and became again a pupil of Gazes at Syra, where he became acquainted with the Rev. Josiah Brewer, a missionary of the American Board of Foreign Missions, who invited him to go to the United States, and by the advice of Gazes the imitation was accepted.

"Sophocles arrived at Boston in 1828 and put himself under the tuition of Mr. Colton of Monson, Massachusetts. In 1829, he entered as freshman at Amherst College, but remained only a part of one year. He afterwards lived at Hartford and New Haven. All his earlier works were published at Hartford, where at one time he taught mathematics. In 1842, he came to Harvard College as tutor in Greek, and remained till 1845. He returned in 1847 to take the same office. Since that time the college apartment in which he died, No. 2 Holworthy, was his only home, serving as dining room and kitchen the greater part of the time, as well as lodging and study. In 1859, he was made assistant professor of Greek; and in 1860 a new professorship of Ancient, Byzantine, and Modern Greek was created for him, which he continued to fill until his death in 1883. This professorship has since been abolished. He received the honorary degree of A.M. from Yale and Harvard, and that of LL.D. from Western Reserve and Harvard.

"He published a number of grammatical books, but his great work was the "Greek Lexicon of the Roman and Byzantine Periods from B.C. 146 to A.D. 1100." This tremendous work of 1187 pages gives reference to 500 authors, not including those referred to of earlier periods.

"Professor Sophocles was a scholar of extraordinary attainments. His knowledge of the Greek literature in its whole length and breadth could hardly be surpassed, and he had much rare and profound erudition on many points on which western scholarship is most weak. On the other hand he treated the classic philology of Germany with neglect, if not with contempt, and he never learned German so as to read it with facility. But many things which are found in the works of German scholars came to Sophocles independently.

”He showed little or no sympathy with the attempts to resuscitate the ancient forms of Greek in the literary language of the new kingdom of Greece; indeed, for this indifference, and for his general lack of interest in the progress of Greece since the Revolution, he was often censured by his fellow countrymen. But much of this, as well as much of his show of indifference to the ordinary calls of humanity, was a part of his habitual cynicism, which was quite as much affected as real. While he refused to take part in the ordinary charities, he was really in his own way one of the most benevolent of men; and it may be doubted whether there was another man in our community whose gifts bore so large a proportion to his personal expenses. Many are the poor who will miss his unostentatious benevolence now that he is gone.

"Though he took little interest in any religious questions, he always remained faithful in name to the Greek Church in which he was born. In later years, he renewed his relations with the monks of Mount Sinai; and as his strength failed, he wandered back more and more in his thoughts to the Sacred Mountain. The monastery of St. Catherine was enriched by more than one substantial present by his kindness; and the pious monks offered solemn prayers on Mount Sinai daily for his recovery from his last sickness, and sent him their congratulations by Atlantic cable on his saint's day. Now that he has left us, we feel that a bond is suddenly broken which connected us with a world which lies beyond our horizon. Such a phenomenon as Sophocles is indeed rare in our academic circles, and we feel that it was a privilege to have him among us."

In 1908, George Herbert Palmer wrote the following in tribute to the memory of Evangelinus Apostolides Sophocles:

"On the 17th of December, 1883, Evangelinus Apostolides Sophocles, Professor of Ancient, Byzantine and Modern Greek in Harvard University, died at Cambridge, in the corner room of Holworthy Hall which he had occupied for nearly forty years. A past generation of American schoolboys knew him gratefully as the author of a compact and lucid Greek grammar. College students -- probably as large a number as ever sat under an American professor --were introduced by him to the poets and historians of Greece. Scholars of a riper growth, both in Europe and America, have wondered at the precision and loving diligence with which, in his dictionary of the later and Byzantine Greek, he assessed the corrupt literary coinage of his native land. His brief contributions to the Nation and other journals were always noticeable for exact knowledge and scrupulous literary honesty. As a great scholar, therefore, and one who through a long life labored to beget scholarship in others, Sophocles deserves well of America. At a time when Greek was usually studied as the schoolboy studies it, this strange Greek came among us, connected himself with our oldest university, and showed us an example of encyclopaedic learning, and such familiar and living acquaintance with Homer and Aeschylus -- yes, even with Polybius, Lucian and Athenaeus -- as we have with Tennyson and Shakespeare and Burke and Macaulay.

"More than this, he showed us how such learning is gathered. To a dozen generations of impressible college students he presented a type of an austere life directed to serene ends, a life sufficient for itself and filled with a never hastening diligence which issued in vast mental stores …

"This man, then, by birth, training, and temper a solitary; whose heritage was Mt. Olympus, and the monastery of Justinian, and the Greek quarter of Cairo, and the isles of Greece; whose intimates were Hesiod and Pindar and Arrian and Basilides, -- this man it was who, from 1842 onward, was deputed to interpret to American college boys the hallowed writings of his race. Thirty years ago too, at the period when I sat on the green bench in front of the long-legged desk, college boys were boys indeed. They had no more knowledge than the high school boy of today, and they were kept in order by much the same methods. Thus, it happened, by some jocose perversity in the arrangement of human affairs, that throughout our Sophomore and Junior years we sportive youngsters were obliged to endure Sophocles, and Sophocles was obliged to endure us. No wonder if he treated us with a good deal of contempt. No wonder that his power of scorn, originally splendid, enriched itself from year to year. We learned, it is true, something about everything except Greek; and the best thing we learned was a new type of human nature. Who that was ever his pupil will forget the calm bearing, the occasional pinch of snuff, the averted eye, the murmur of the interior voice, and the stocky little figure with the lion's head. There is the corner he stood, as stranded and solitary as the Egyptian obelisk in the hurrying Place de la Concorde. In a curious sense of fashion, he was faithful to what he must have felt an obnoxious duty. He was never absent from his post, nor did he cut short the hours, but he gave us only such attention as was nominated in the bond; ...

"How much of this cynicism of conduct and of speech was genuine perhaps he knew as little as the rest of us; but certainly it imparted a pessimistic tinge to all he did and said. To hear him talk, one would suppose the world was ruled by accident or by an utterly irrational fate; for in his mind the two conceptions seemed closely to coincide. His words were never abusive; they were deliberate, peaceful even; but they made it very plain that so long as one lived there was no use in expecting anything. Paradoxes were a little more probable than ordered calculations; but even paradoxes would fail. Human beings were altogether impotent, though they fussed and strutted as if they could accomplish great things. How silly was trust in men's goodness and power, even in one's own! Most men were bad and stupid, -- Germans especially so. The Americans knew nothing, and never could know. A wise man would not try to teach them. Yet some persons dreamed of establishing a university in America! Did they expect scholarship where there were politicians and business men? Evil influences were far too strong. They always were. The good were made expressly to suffer, the evil to succeed. Better leave the world alone, and keep one's self true. 'Put a drop of milk into a gallon of ink; it will make no difference. Put a drop of ink into a gallon of milk; the whole is spoiled.'

"In the last days of his life, it is true, when his thoughts were oftener in Arabia than in Cambridge, he once or twice referred to 'the ambition of learning' as the temptation which had drawn him out from the monastery, and had given him a life less holy than he might have led among the monks. But these were moods of humility rather than of regret. Habitually he maintained an elevation above circumstances, -- was it Stoicism or Christianity? -- which imparted to his behavior, even when most eccentric, an unshakable dignity. When I have found him in his room, curled up in shirt and drawers, reading the 'Arabian Nights,' the Greek service book, or the 'Ladder of the Virtues' by John Klimakos, he has risen to receive me with the bearing of an Arab sheikh, and has laid by the Greek folio and motioned me to a chair with a stateliness not natural to our land or century. It would be clumsy to liken him to one of Plutarch's men; for though there was much of the heroic and extraordinary in his character and manners, nothing about him suggested a suspicion of being on show. The mold in which he was cast was formed earlier. In his bearing and speech, and in a certain large simplicity of mental structure, he was the most Homeric man I ever knew."

E.A. Sophocles: A Second Sophocles

Evangelinus Apostolides Sophocles – to give him his full sounding name – was a very exceptional man, having many pleasant acquaintances, but not one intimate friend; he lived always in one of the Harvard dormitories, and was almost as recluse as a monk in his cell.

He spent little money upon himself, but gave freely when he saw need, He found his native Grecian village suffering for want of water, and he gave them as a memorial a complete system of water works; this was known, from the necessity of the case, but he objected to any publicity, and most of all to the publicity of philanthropist. He desired to "do good by stealth," and it would have pained him at any time "to find it fame." The pupils at Harvard in recent years have not known the best of Professor Sophocles, who was indeed never so goou 10 start the boys in GreeK as he was to carry them on in advanced studies, where he was richly furnished to stimulate their efforts. To illustrate the eccentric character of his thought it is told that he mentioned as the three best books the Bible, Don Quixote and the Arabian Nights as comprising the whole philosophy of life. This Is almost as strange a collocation as Hie old gambling English parson's, who would be buried with the prayer-book and a pack of cards under bis bolster.

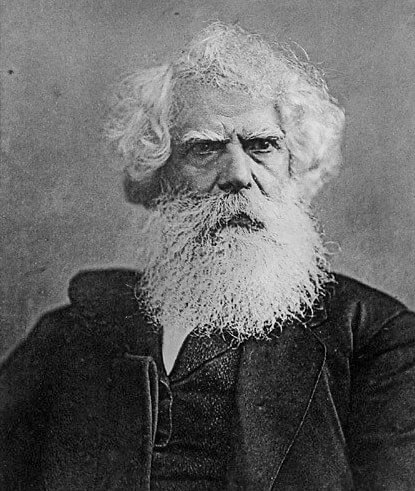

In person the venerable professor was short. but his bushy, snow-white hair and venerable beard, his olive complexion and dark eyes of Oriental lustre, his measured speech and dignity of motion made him resemble more an Arab Sheik, like Abraham of old, than the American university professor. His long residence in ihis country and his continual study of language had given him the power of using English without the slightest foreign accent, which Is more than can bo said of either the elder or the younger Agassiz. Beneath a reserved exterior he had a gentle heart and his manners were simple as those of a child; yet ho was pronounced by Dr. A. P. Peabody the "most learned man at the university."

He boarded himself and indulged in Turkish dishes which could not be obtained in a Cambridge boarding house. He never married, and though he allowed the "goody" to visit his room for the purpose of making tho bed, he was so averse to the disturbances caused by these domestics in sweeping that he would go from October till commencement In June without allowing the carpet to be touched by the broom.

Source: "A Second Sophocles." The New York Times, 23 December 1883, p. 14.

A Daily Lesson in History

The Boston Globe (April 16, 1903)

Professor Sophocles, who was connected as teacher of Greek with Harvard college for more than 40 years, was one of the most interesting characters whose talents are embalmed In the annals of that great institution. Born in Greece, his youth was spent among the monks of the Greek convent on Mt Sinai, and throughout his long life he never departed from the rigid asceticism in which he was practiced as a youth amid those monastic scenes.

Under the auspices of the American board for foreign missions he came to America in his 22nd year. For some years he taught Greeek at Amherst. Massachusetts, and Hartford and New Haven, Connecticut.

In 1842 … he became connected with Harvard university. He began his eareer there as a tutor, and afterward became assistant professor. In I860, at the age of 53, he was appointed professor of modern and Byzantine Greek. And this office he held until his death. 23 years later.

Professor Sophocles was one of the most remarkable Greek scholars of his time. But his influence was less apparent among the undergraduate students of the university than among the more advanced scholars. He was a man of extraordinary simplicity and severity of life. President Felton of Harvard university, who was as intimately acquainted as any other man of Cambridge with his habits, confessed that he knew practically nothing of the professor's personal history. For nearly 40 years Professor Sophocles lived alone in No. 3 Holworthy Hall, and while he was not averse to occasional discourse with the eminent men of Cambridge who were contemporaneous with him at Cambridge, it is said that he enjoyed no company so much as he did that of his chickens, which he reared with infinite solicitude and preoccupation.

His habits of life were such that he exhausted only a small part of his income, and yet withal he was not in any sense a miser. He gave liberally, but secretly, to charities, and to his native village in Greece he contributed the means for the establishment of a system of public water works, the necessity for which he had observed on one of the several visits that he paid to his birthplace.

His memory was prodigious, and it iss aid that he knew the "Arabian Nights" by heart. He once declared that the three greatest books in the world were the Bible, the "Arabian Nights" and "Oon Quixote."

So little as known of the personal history of Professor Sophocles that it is even said that his original name was not that which he bore in this country. He wvs extremely sensitive about his age and never directly told any one how old he was. but in his later years often decleared that he was nearing his 100th anniversary.

He wrote manv works, all of them text books in the Greek language. His most notable work was the "Greek lexicon of the Roman and Bvzantine Period," published in 1870.

Source: "A Daily Lesson in History." The Boston Globe, 16 April 1903, p. 8.

Greek With a Word For It

On Tuesday June 27, 1950, the Wall Street Journal published the "Greek With a Word For It" about Professor Evangelinus Apostolides Sophocles:

One of the most delightful attributes of the whimsical Professor Evangelinus Apostolides Sophocles, who emigrated to America to become Professor of Greek at Harvard, has wholehearted propensity for cutting corners.

One day meeting Prof. Shaler crossing Harvard Yard, Prof. Sophocles inquired about the sheaf of papers his colleague was carrying under his arm.

"Oh, those are examination papers," Shaler replied. "I've got to read and mark the pesky things!"

"Oh, I never do that!" Professor Sophocles protested. "After a boy has been in one's class a few weeks you can know just about what he can do. If he doesn't come up to his average performance in his exam, you know it's an accident."

"But what if exceeds it?" Shaler wanted to know.

"Oh," laughed Professor Sophocles, "then he's cheating!"

Source: "Greek With a Word For It." The Wall Street Journal, 27 June 1950, p. 5.

The Glory That is Cambridge

"The Glory That is Cambridge" written by Frances H. Eliot, daughter-in-law of former Harvard University President Charles William Eliot, included the following excerpt regarding Professor Evangelinus Apostolides Sophocles:

… Of all the strange and interesting characters at Harvard at that time, the most fascinating was Professor Evangelinus Apostolides Sophocles, a bachelor who lived a solitary life. But he kept hens in the yard of Fay House, now one of the buildings of Radcliffe College. He loved his "cockerels and pullets" as he called them -- and named the pullets after the Cambridge ladies who had befriended him and invited him to meals.

As eggs appeared, he would write on each one the name of the hen that laid it, and when from time to time he would bring an offering of a basket of fresh eggs to my husband's father and mother, the two small boys -- my husband and his brother -- would sort the eggs according to the names written on them, for they too had their favorites among the Cambridge ladies.

I can remember only Professor Sophocle's personal appearance -- piercing black eyes under shaggy eyebrows, a shock of white hair, and the great unkempt beard and whiskers.

Source: Eliot, Frances H. "A Daily Lesson in History." Atlantic Monthly, September 1945.

George Herbert Palmer student of Professor Sophocles, and professor at Harvard University, wrote the following in 1891.

Reminiscences of Professor Sophocles

On the 14th of February, 1883, Evan gelinus Apostolides Sophocles, Professor of Ancient, Byzantine, and Modern Greek in Harvard University, died at Cambridge, in the corner room of Holworthy Hall which he had occupied for nearly forty years. A past generation of American school-boys knew him gratefully as the author of a compact and lucid Greek grammar. College students – probably as large a number as ever sat under an American professor – have been introduced by him to the poets and historians of Greece. Scholars of a riper growth, both in Europe and America, wonder at the precision and loving diligence with which, in his dictionary of the later and Byzantine Greek, he assessed the corrupt literary coinage of his native land. His brief contributions to The Nation and other journals were always noticeable for exact know ledge and scrupulous literary honesty.

As a great scholar, therefore, and one who through a long life labored to be get scholarship in others, Sophocles deserves well of America. At a time when Greek was usually studied as the school boy studies it, this strange Greek came among us, connected himself with our oldest university, and showed us an example of encyclopaedic learning, and such familiar and living acquaintance with Homer and AEschylus – yes, even with Polybius, Lucian, and Athenaeus – as we have with Tennyson and Shakespeare and Burke and Macaulay. More than this, he showed us how such learning was gathered. To a dozen generations of impressible college students he presented a type of an austere life directed to serène ends, a life sufficient for itself and filled with a never-hastening diligence which issued in vast mental stores.

It is not, however, the purpose of this paper to trace the influence over American scholarship of this hardly domesticated wise man of the East. Nor will there be any attempt to narrate the outward events of his life. These are not fully known; and could they be discovered, there would be a kind of impiety in reporting them. Few traits were so characteristic of him as his wish to conceal his history. His motto might have been that of Epicurus and Descartes: "Well hid is well lived." Yet in spite of his concealments, perhaps in part because of them, few persons ever connected with Harvard have left behind them an impression of such massive individuality. He was long a notable figure in university life, one of those picturesque characters who by their very being give impulse to aspiring mortals and check the ever-encroaching commonplace. It is ungrateful to allow one formerly so stimulating and talked about to go out into silence. Now that the decent interval after death is passed, a memorial to this unusual man may be reverently set up. His likeness may be drawn by a fond, though faithful hand. Or at least such stories about him may be kindly put into the record of print as will reflect some of those rugged, paradoxical, witty, and benignant aspects of his nature which marked him off from the humdrum herd of men.

My own first approach to Sophocles was at the end of my Junior year in college. It was necessary for me to be absent from his afternoon recitation. In those distant days absences were regarded by Harvard law as luxuries, and a small fixed quantity of them, a sort of sailor's grog, was credited with little charge each half year to every student. I was already nearing the limit of the unenlargeable eight, and could not well venture to add another to my score. It seemed safer to try to win indulgence from my fierce-eyed instructor. Early one morning I went to Sophocles's room.

"Professor Sophocles," I said, "I want to be excused from attending the Greek recitation this afternoon."

"I have no power to excuse," uttered in the gruffest of tones, while he looked the other way.

"But I cannot be here. I must be out of town at three o'clock."

"I have no power. You had better see the president."

Finding the situation desperate, I took a desperate leap.

"But the president probably would not allow my excuse. At the play of the Hasty Pudding Club tonight I am to appear as leading lady. I must go to Brookline this afternoon and have my sister dress me."

No muscle of the stern face moved; but he rose, walked to a table where his class lists lay, and, taking up a pencil, calmly said: "You had better say nothing to the president. You are here now. I will mark you so."

He sniffed, he bowed, and, without smile or word from either of us, I left the room.

As I came to know Sophocles after wards, I found that in this trivial early interview I had come upon some of the most distinctive traits of his character; here was an epitome of his brusquerie, his dignity, his whimsical logic, and his kind heart.

Outwardly he was always brusque and repellent. A certain savagery marked his very face. He once observed that, in introducing a character, Homer is apt to draw attention to the eye. Certainly in himself this was the feature which first attracted notice; for his eye had uncommon alertness and intelligence. Those who knew him well detected in it a hidden sweetness; but against the stranger it burned and glared, and guarded all avenues of approach. Startled it was, like the eye of a wild animal, and penetrating, "peering through the portals of the brain like the brass cannon." Over it crouched bushy brows, and all around the great head bristled white hair, on forehead, cheeks, and lips, so that little flesh remained visible, and the life was settled in two fiery spots. This concentration of expression in the few elementary features of shape, hair, and eyes made the head a magnificent subject for painting. Rembrandt should have painted it. William Hunt would have done it best justice among our own painters. It is a pity that no report of it hangs in Memorial Hall. But he would never allow a portrait of himself to be drawn. Into his personality strangers must not intrude.

Venturing once to try for memoranda of his face, I took an artist to his room. The courtesy of Sophocles was too stately to allow him to turn my friend away, but he seated himself in a shaded window, and kept his head in constant motion. When my frustrated friend had departed, Sophocles told me, though without direct reproach, of two sketches which had before been surreptitiously made, – one by the pencil of a student in his class, another in oils by a lady who had followed him on the street. Toward photography his aversion was weaker; perhaps because in that art a human being less openly meddled with him. Several admirable photographs of him exist.

From this sense of personal dignity, which made him at all times determined to keep out of the grasp of others, much of his brusqueness sprang. On the morning after he returned from his visit to Greece a fellow-professor saw him on the opposite side of the street, and, has tening across, greeted him warmly :

"So you have been home, Mr. Sophocles; and how did you find your mother?"

"She was up an apple-tree," said Sophocles, confining himself to the facts of the case.

A boy who snowballed him on the street he prosecuted relentlessly, and he could not be appeased until a considerable fine was imposed; but he paid the fine himself. Many a bold push was made to ascertain his age; yet, however suddenly the question came, or however craftily one crept from date to date, there was a uniform lack of success.

"I see Allibone's Dictionary says you were born in 1805," a gentleman remarked.

"Some statements have been nearer, and some have been farther from the truth."

One day, when a violent attack of illness fell on him, a physician was called for diagnosis. He felt the pulse, he examined the tongue, he heard the report of the symptoms, then suddenly asked, "How old are you, Mr. Sophocles?" With as ready presence of mind and as pretty ingenuity as if he were not lying at the point of death, Sophocles answered:

"The Arabs, Dr. W., estimate age by several standards. The age of Hassan,the porter, is reckoned by his wrinkles; that of Abdallah, the physician, by the lives he has saved; that of Achmet, the sage, by his wisdom. I, all my life a scholar, am nearing my hundredth year."

To those who had once come close to Sophocles these little reserves, never asserted with impatience, were characteristic and endearing. I happen to know his age; hot irons shall not draw it from me.

Closely connected with his repellent reserve was the stern independence of his modes of life. In his scheme, little things were kept small and great things large. What was the true reading in a passage of Aristophanes, what the usage of a certain word in Byzantine Greek, – these were matters on which a man might well reflect and labor. But of what consequence was it if the breakfast was slight or the coat worn? Accordingly, a single room, in which a light was seldom seen, sufficed him during his forty years of life in the college yard. It was totally bare of comforts. It contained no carpet, no stuffed furniture, no bookcase. The college library furnished the volumes he was at any time using, and these lay along the floor, beside his dictionary, his shoes, and the box that contained the sick chicken. A single bare table held the book he had just laid down, together with a Greek newspaper, a silver watch, a cravat, a paper package or two, and some scraps of bread. His simple meals were prepared by himself over a small open stove, which served at once for heat and cookery. Eating, however, was always treated as a subordinate and incidental business, deserving no fixed time, no dishes, nor the setting of a table. The peasants of the East, the monks of Southern monasteries, live chiefly on bread and fruit, relished with a little wine; and Sophocles, in spite of Cambridge and America, was to the last a peasant and a monk. Such simple nutriments best fitted his constitution, for "they found their acquaintance there."

The Western world had come to him by accident, and was ignored; the East was in his blood, and ordered all his goings. Yet, as a grave man of the East might, he had his festivities, and could on occasion be gay. Among a few friends he could tell a capital story and enjoy a well-cooked dish. But his ordinary fare was meagre in the extreme. For one of his heartier meals he would cut a piece of meat into bits and roast it on a spit, as Homer's people roasted theirs.

"Why not use a gridiron?" I once asked.

"It is not the same," he said. "The juice then runs into the fire. But when I turn my spit it bastes itself."

His taste was more than usually sensitive, kept fine and discriminating by the restraint in which he held it. Indeed, all his senses, except sight, were acute. The wine he drank was the delicate unresinated Greek wine, – Corinthian, or Chian, or Cyprian; the amount of water to be mixed with each being carefully debated and employed. Each winter a cask was sent him from a special vineyard on the heights of Corinth, and occasioned something like a general rejoicing in Cambridge, so widely were its flavorous contents distributed. Whenever this cask arrived, or when there came a box from Mt. Sinai filled with potato-like sweetmeats, – a paste of figs, dates, and nuts, stuffed into sewed goatskins, – or when his hens had been laying a goodly number of eggs, then under the blue cloak a selection of bottles, or of sweet meats, or of eggs would be borne to a friend's house, where for an hour the old man sat in dignity and calm, opening and closing his eyes and his jack-knife; uttering meanwhile detached remarks, wise, gruff, biting, yet seldom lacking a kernel of kindness, till bedtime came, nine o'clock, and he was gone, the gifts –if thanks were feared – left in a chair by the door. There were half a dozen houses and dinner tables in Cambridge to which he went with pleasure, houses where he seemed to find a solace in the neighborhood of his kind. But human beings were an exceptional luxury. He had never learned to expect them. They never became necessities of his daily life, and I doubt if he missed them when they were absent. As he slowly recovered strength, after one of his later illnesses, I urged him to spend a month with me. Refusing in a brief sentence, he added with unusual gentleness: "To be alone is not the same for me and for you else."

Unquestionably, much of his disposition to remain aloof and to resist the on-coming intruder was bred by the experiences of his early youth. His native place, Tsangarada, is a village of eastern Thessaly, far up among the slopes of the Pindus. Thither, several centuries ago, an ancestor led a migration from the west coast of Greece, and sought a refuge from Turkish oppression. From generation to generation his fathers continued to be shepherds of their people, the office of Proëstos, or governor, being hereditary in the house. Sturdy men those ancestors must have been, and picturesque their times. In late winter afternoons, at 3 Holworthy, when the dusk began to settle among the elms about the yard, legends of these heroes and their faroff days would loiter through the exile's mind. At such times bloody doings would be narrated with all the coolness that appears in Caesar's Commentaries, and over the listener would come a sense of a fantastic world as different from our own as that of Bret Harte's Argonauts.

One evenging: "My great-grandfather was not easily disturbed. He was a young man and Proëstos. His stone house stood apart from the others. He was sitting in its great room one evening, and heard a noise. He looked around, and saw three men by the farther door. 'What are you here for?' 'We have come to assassinate you.' 'Who sent you?' 'Andreas'. It was a political enemy. 'How much did Andreas promise you?' 'A dollar.' 'I will promise you two dollars if you will go and assassinate Andreas.' So they turned, went, and assassinated Andreas. My great-grandfather went to Scyros the next day, and remained there five years. In five years these things are forgotten in Greece. Then he came back, and brought a wife from Scyros, and was Proëstos once more."

Another evening: "People said my grandfather died of leprosy. Perhaps he did. As Proëstos he gave a decision against a woman, and she hated him. One night she crept up behind the house, where his clothes lay on the ground, and spread over his clothes the clothes of a leper. After that, he was not well. His hair fell off, and he died. But perhaps it was not leprosy; perhaps he died of fear. The Knights of Malta were worrying the Turks. They sailed into the harbor of Volo, and threatened to bombard the town. The Turks seized the leading Greeks and shut them up in the mosque. When the first gun was fired by the frigate, the heads of the Greeks were to come off. My grandfather went into the mosque a young man. A quarter of an hour afterwards the gun was heard, and my grandfather waited for the headsman. But the shot toppled down the minaret, and the Knights of Malta were so pleased that they sailed away, satisfied. The Turks, watching them, forgot about the prisoners. But two hours later, when my grandfather came out of the mosque, he was an old man. He could not walk well. His hair fell off, and he died."

Sometimes I caught glimpses of Turkish oppression in times of peace.

"I remember the first time I saw the wedding gift given. No new-made bride must leave the house she visits without a gift. My mother's sister married, and came to see us. I was a boy. She stood at the door to go, and my mother remembered she had not had the gift. There was not much to give. The Turks had been worse than usual, and everything was buried. But my mother could not let her go without the gift. She searched the house, and found a saucer, – it was a beautiful saucer; and this she gave her sister, who took it and went away."

"How did you get the name of Sophocles?" I asked, one evening. "Is your family supposed to be connected with that of the poet?"

"My name is not Sophocles," [the Professor replied.] "I have no family name. In Greece, when a child is born, it is carried to the grandfather to receive a name." (I thought how, in the Odyssey, the nurse puts the infant Odysseus in the arms of his mother's father, Autolycus, for naming.) [The Professor contnued.] "The grandfather gives him his own name. The father's name, of course, is different; and this he too gives when he becomes a grandfather. So in old Greek families two names alternate through generations. My grandfather's name was Evangelinos. This he gave to me; and I was distinguished from others of that name because I was the son of Apostolos, Apostolides. But my best schoolmaster was fond of the poet Sophocles, and he was fond of me. He used to call me his little Sophocles. The other boys heard it, and they began to call me so. It was a nickname. But when I left home people took it for my family name. They thought I must have a family name. I did not contradict them. It makes no difference. This is as good as any."

One morning he received a telegram of congratulation from the monks in Cairo.

"It is my day," he said. "How did the monks know it was your birthday?" I asked. "It is not my birthday. Nobody thinks about that. It is forgotten. This is my saint's day? Coming into the world is of no consequence; coming under the charge of the saints is what we care for. My name puts me in the Virgin's charge, and the feast of the Annunciation is my day. The monks know my name."

To the Greek Church he was always loyal. Its faith had glorified his youth, and to it he turned for strength through out his solitary years. Its conventual discipline was dear to him, and oftener than of his birthplace at the foot of Mt. Olympus he dreamed of Mt. Sinai. On Mt. Sinai the Emperor Justinian founded the most revered of all Greek monasteries. Standing remote on its sacred mountain, the monastery is obliged to depend on Cairo for its supplies. In Cairo, accordingly, there is a branch or agency, which during the boyhood of Sophocles was presided over by his uncle Constantius. At twelve he joined this uncle in Cairo. In the agency there, in the parent monastery on Sinai itself, and in journeyings between the two, the happy years were spent which shaped his intellectual and religious constitution.

Though he never outwardly became a monk, he largely became one within. His adored uncle Constantius was his spiritual father. Through him his ideals had been acquired, – his passion for learning, his hardihood in duty, his imperturbable patience, his brief speech, which allowed only so many words as might scantily clothe his thought, his indifference to personal comfort. He never spoke the name of Constantius without some sign of reverence; and in his will, after making certain private bequests, and leaving to Harvard College all his printed books and stereotype plates, he adds this clause:

"All the residue and remainder of my property and estate I devise and bequeath to the said President and Fellows of Harvard College in trust, to keep the same as a permanent fund, and to apply the income thereof in two equal parts: one part to the purchase of Greek and Latin books (meaning hereby the ancient classics) or of Arabic books, or of books illustrating or explaining such Greek, Latin, or Arabic books; and the other part to the Catalogue Department of the General Library. …. My will is that the entire income of the said fund be expended in every year, and that the fund be kept forever unimpaired, and be called and known as the Constantius Fund, in memory of my paternal uncle, Constantius the Sinaite …"

This man, then, by birth, training, and temper a solitary; whose heritage was Mt. Olympus, and the monastery of Justinian, and the Greek quarter of Cairo, and the isles of Greece; whose intimates were Hesiod and Pindar and Arrian and Basilides, – this man it was who, from 1842 onward, was deputed to interpret to American college boys the hallowed writings of his race. Thirty years ago, too, at the period when I sat on the green bench in front of the long-legged desk, college boys were boys indeed. They had no more knowledge than the high-school boy of to-day, and they were kept in order by much the same methods. Thus it happened, by some jocose perversity in the arrange ment of human affairs, that throughout our Sophomore and Junior years we sportive youngsters were obliged to endure Sophocles, and Sophocles was obliged to endure us. No wonder if he treated us with a good deal of contempt. No wonder that his power of scorn, originally splendid, enriched itself from year to year. We learned, it is true, something about everything except Greek; and the best thing we learned was a new type of human nature. Who that was ever his pupil will forget the calm bearing, the occasional pinch of snuff, the averted eye, the murmur of the interior voice, and the stocky little figure with the lion's head? There in the corner he stood, as stranded and solitary as the Egyptian obelisk in the hurrying Place de la Concorde. In a curious sort of fashion he was faithful to what he must have felt an obnoxious duty. He was never absent from his post, nor did he cut short the hours, but he gave us only such attention as was prescribed in the bond; he appeared to hurry past, as by set purpose, the beauties of what we read, and he took pleasure in snubbing expectancy and aspiration.

"When I entered college," says an eminent Greek scholar, "I was full of the notion, which I probably could not have justified, that the Greeks were the greatest people that had ever lived. My enthusiasm was fanned into a warmer glow when I learned that my teacher was himself a Greek, and that our first lesson was to be the story of Thermopylae. After the passage of Herodotus had been duly read, Sophocles began: 'You must not suppose these men stayed in the Pass because they were brave; they were afraid to run away.' A shiver went down my back. Even if what he said had been true, it ought never to have been told to a Freshman."

The universal custom of those days was the hearing of recitations, and to this Sophocles conformed so far as to set a lesson, and to call for its translation bit by bit. But when a student had read his suitable ten lines, he was stopped by the raised finger; and Sophocles, fixing his eyes on vacancy, and taking his start from some casual suggestion of the passage, began a monologue, – a monologue not unlike one of Browning's in its caprices, its involvement, its adaptation to the speaker's mind rather than to the hearer's, and its ease in glancing from heaven to earth, from earth to heaven. During these intervals the sluggish slumbered, the industrious devoted themselves to books and papers brought in the pocket for the purpose, the dreamy enjoyed the opportunity of wondering what the strange words and their still stranger utterer might mean. The monologue was sometimes long and sometimes short, according as the theme which had been struck kindled the rhapsodist, and enabled him, with greater or less completeness, to forget his class. When some subtlety was approached, a smile – the only smile ever seen on his face by strangers – lifted for a moment the corner of the mouth. The student who had been reciting stood meanwhile, but sat when the voice stopped, the white head nodded, the pencil made a record, and a new name was called.

There were perils, of course, in records of this sort. Reasons for the figures which subsequently appeared on the college books were not easy to find. Some of us accounted for our marks by the fact that we had red hair or long noses; others preferred the explanation that our professor's pencil happened to move more readily to the right hand or to the left. For the most part we took good naturedly whatever was given us, though questionings would sometimes arise. A little before my time there entered an ambitious young fellow, who cherished large purposes in Greek. At the end of the first month under his queer instructor he went to the regent and inquired for his mark in Plato. It was three, the maximum being eight. Horror stricken, he penetrated Sophocles's room.

"Professor Sophocles," he said, "I find my mark is only three. There must be some mistake. There is another Jones in the class, you know, J. S. Jones" (a lump of flesh), "and may it not be that our marks have been confused?" An unmoved countenance, a little wave of the hand, accompanied [Professor Sophocles's] answer: "You must take your chance, – you must take your chance."

In my own section, when anybody was absent from a certain bench, poor Prindle was always obliged to go forward and say, "I was here today, Professor Sophocles," or else the gap on the bench where six men should sit was charged to Prindle's account. In those easy-going days, when men were examined for entrance to college orally and in squads, there was a good deal of eagerness among the knowing ones to get into the squad of Sophocles; for it was believed that he admitted everybody, on the ground that none of us knew any Greek, and it was consequently unfair to discriminate.

"Do you read your examination books?" he once asked a fellow-instructor. "If they are better than you expect, the writers cheat; if they are no better, time is wasted." "Is to-day story day or contradiction day?" he is reported to have said to one who, in the war time, eagerly handed him a newspaper, and asked if he had seen the morning's news.

How much of this cynicism of conduct and of speech was genuine perhaps he knew as little as the rest of us; but certainly it imparted a pessimistic tinge to all he did and said. To hear him talk, one would suppose the world was ruled by accident or by an utterly irrational fate; for in his mind the two conceptions seemed closely to coincide. His words were never abusive; they were deliberate, peaceful even; but they made it very plain that as long as one lived there was no use in expecting any thing. Paradoxes were a little more probable than ordered calculations; but even paradoxes would fail. Human beings were altogether impotent, though they fussed and strutted as if they could accomplish great things. How silly was trust in men's goodness and power, even in one's own Most men were bad and stupid, – Germans especially so. The Americans knew nothing, and never could know. A wise man would not try to teach them. Yet some persons dreamed of establishing a university in America! Did they expect scholarship where there were politicians and business men? Evil influences were far too strong. They always were. The good were made expressly to suffer, the evil to succeed. Better leave the world alone, and keep one's self true. "Put a drop of milk into a gallon of ink; it will make no difference. Put a drop of ink into a gallon of milk; the whole is spoiled."

I have felt compelled to dwell at some length on these cynical, illogical, and austere aspects of Sophocles's character, and even to point out the circumstances of his life which may have shaped them, because these were the features by which the world commonly judged him, and was misled. One meeting him casually had little more to judge by. So entire was his reserve, so little did he permit close conversation, so seldom did he raise his eye in his slow walks on the street, so rarely might a stranger pass the bolted door of his chamber, that to the last he bore to the average college student the character of a sphinx, marvelous in self-sufficiency, amazing in erudition, romantic in his suggestion of distant lands and customs, and for ever piquing curiosity by his eccentric and sarcastic sayings. All this whimsicality and pessimism would have been cheap enough, and little worth recording, had it stood alone. What lent it price and beauty was that it was the utterance of a singularly self-denying and tender soul. The incongruity between his bitter speech and his kind heart endeared both to those who knew him. Like his venerable cloak, his grotesque language often hid a bounty underneath. For he was never weary in well-doing. How many students have received his surly benefactions! In how many small tradesmen's shops did he have his appointed chair! His room was bare: but in his native town an aqueduct was built; his importunate and ungrateful relatives were pensioned; the monks of Mt. Sinai were protected against want; the children and grandchildren of those who had befriended his early years in America were watched over with a father's love; and by care for helpless creatures wherever they crossed his path he kept himself clean of selfishness.

One winter night, at nearly ten o'clock, I was called to my door. There stood Sophocles. When I asked him why he was not in bed an hour ago,

"A. has gone home," he said.

"I know it," I answered; for A. was a young instructor dear to me.

"He is sick," he went on.

"Yes."

"He has no money."

"Well, we will see how he will get along."

"But you must get him some money, and I must know about it."

And he would not go back into the storm – this graybeard professor, solicitous for an overworked tutor – till I assured him that arrangements had been made for continuing A.'s salary during his absence. I declare, in telling the tale I am ashamed. Am I wronging the good man by disclosing his secret, and saying that he was not the cynical curmudgeon for which he tried to pass? But already before he was in his grave the secret had been discovered, and many gave him persistently the love which he still tried to wave away.

Toward dumb and immature creatures his tenderness was more frank, for these could not thank him. Children always recognized in him their friend. A group of curly-heads usually appeared in his window on Class Day. A stray cat knew him at once, and, though he seldom stroked her, would quickly accommodate herself near his legs. By him spiders were watched, and their thin wants supplied. But his solitary heart went out most unreservedly and with the most pathetic devotion toward fragile chickens; and out of these uninteresting little birds he elicited a degree of responsive intelligence which was startling to see. One of his dearest friends, coming home from a journey, brought him a couple of bantam eggs. When hatched and grown, they developed into a little five-inch burnished cock, which shone like a jewel or a bird of paradise, and a more sober but exquisite hen. These two, Frank and Nina, and all their numerous progeny for many years, Sophocles trained to the hand. Each knew its name, and would run from the flock when its white-haired keeper called, and, sitting upon his hand or shoulder, would show queer signs of affection, not hesitating even to crow. The same generous friend who gave the eggs gave shelter also to the winged consequences. And thus it happened that three times a day, as long as he was able to leave his room, Sophocles went to that house where the Harvard Annex is now sheltered to attend his pets. White grapes were carried there, and the choicest of corn and clamshell; and endless study was given to devising conveniences for housing, nesting, and the promenade. But he did not demand too much from his chickens.

In their case, as in dealing with human beings, he felt it wise to bear in mind the limit and to respect the fore ordained. When Nina was laying badly, one springtime, I suggested a special food as a good egg-producer. But Sophocles declined to use it. "You may hasten matters," he said, "but you cannot change them. A hen is born with just so many eggs to lay. You cannot increase, the number." The eggs, as soon as laid, were penciled with the date and the name of the mother, and were then distributed among his friends, or sparingly eaten at his own meals. To eat a chicken itself was a kind of cannibalism from which his whole nature shrank. "I do not eat what I love," he said, rejecting the bowl of chicken broth I pressed upon him in his last sickness.

If in ways so uncommon his clinging nature, cut off from domestic opportunity, went out to unresponsive creatures, it may be imagined how good cause of love he furnished to his few intimates among mankind. They found in him sweet courtesy, undemanding gentleness, an almost feminine tact in adapting what he could give to what they might receive. To their eyes the great scholar, the austere monk, the bizarre professor, the pessimist, were hidden by the large and lovable man. Even strangers recognized him as no common person, so thoroughly was all he did and said purged of superfluity, so veracious was he, so free from apology. His everyday thoughts were worthy thoughts. He knew no shame or fear, and had small wish, I think, for any change. Always a devout Christian, he seldom used expressions of regret or hope. Probably he concerned himself little with these or other feelings. In the last days of his life, it is true, when his thoughts were oftener in Arabia than in Cambridge, he once or twice referred to "the ambition of learning" as the temptation which had drawn him out from the monastery, and had given him a life less holy than he might have led among the monks. But these were moods of humility rather than of regret.

Habitually he maintained an elevation above circumstances, – was it stoicism or Christianity? – which imparted to his behavior, even when most eccentric, an unshakable dignity. When I have found him in his room, curled up in shirt and drawers, reading the Arabian Nights, the Greek service book, or the Ladder of the Virtues, by John Klimakos, he has risen to receive me with the bearing of an Arab sheikh, and has laid by the Greek folio and motioned me to a chair with a stateliness not natural to our land or century.

It would be clumsy to liken him to one of Plutarch's men; for though there was much of the heroic and extraordinary in his character and manners, nothing about him suggested a suspicion of being on show. The mould in which he was cast was formed earlier. In his bearing and speech, and in a certain large simplicity of mental structure, he was the most Homeric man I ever knew.

Source: Palmer, George Herbert. "Reminiscences of Professor Sophocles." The Atlantic Monthly, 1891, pp. 779 - 788.

George Herbert Palmer (March 9, 1842 – May 7, 1933) was an American scholar and author. He was a graduate, and then professor at Harvard University. He is also known for his published works, like the translation of "The Odyssey" (1884) and others about education and ethics, such as "The New Education" (1887) and "The Glory of the Imperfect" (1898).

E.A Sophocles Curriculum Vitae

EDUCATION

Monastery of St. Catherine (Mt. Sinai)

Monson Academy (Monson, Massachusetts)

Amherst College, 1829

Case Western Reserve College (LL.D.), 1862

Harvard, 1868

PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE

Greek Teacher, Mt. Pleasant Classical Institute (later Amherst Academy), 1830 - 1834

Instructor of Mathematics, Hartford, Connecticut, 1834

Instructor of Greek, Yale, 1837-40

Assistant Professor of Greek, Harvard, 1842 - 1860

Professor of Modern and Byzantine Greek, Harvard, 1860 - 1883

PUBLICATIONS

A Greek Grammar for the Use of Learners (Hartford, 1835);

Romaic Grammar (Hartford, 1842);

A Catalogue of Greek Verbs for the Use of Colleges (Hartford, 1844);

History of the Greek Alphabet and of the Pronunciation of Greek (Cambridge, 1848);

A Glossary of Later and Byzantine Greek (Cambridge, 1860);

Greek Lexicon of the Roman and Byzantine Periods from B.C. 146 to A.D. 1100

Papers: Papers 1837 - 1870 in Harvard archives.

Source: Meyer, Reinhold. "Sophocles, Evangelinos Apostolides" Database of Classical Scholars, Rutgers University

Also:

Evangelinus Apostolides Sophocles: The Ascetic of Harvard College

About the Program of Modern Greek Studies at Harvard University