Christos Evangelides

If I had to characterize [Christos Evangelides] in one sentence, it would be that he was deeply religious and proud of his Greek heritage; the term super-patriot comes to mind.

Constantine G. Hatzidimitriou

Christodoulus Leonidas Miltiades Evangeles (1815 - 1881) – typically known as Christos Evangelides and called Christy by his friends – writes in his diary that his parents were from the Agrapha region of Thessaly and had moved to Thessaloniki where he was born. His father, Evangeles Agraphiotes died in 1819 when he was four years old, and along with his two siblings and mother who had remarried, continued to live Thessaloniki where his maternal grandfather was a priest. They fled the fighting in Thessaloniki and wound up in Smyrna. From there, Christos continued on to Syros with American Protestant missionaries who were delivering aid to the Greeks.

In 1828, he was subsequently brought to the United States by an American sea captain. He arrived in New York on March 21, 1828 at the age of 12. He stayed with Peter Stuyvesant and influential New York banker Samuel Ward before being sent to study at the Mount Pleasant Classical Institute in Amherst, Massachusetts. On his way to Amherst, Christos visited New Haven, Connecticut where he met with Stephanos and Pantelis Galatis, and Constantine and Pandias Rallis. These two sets of brothers from Chios were attending Yale University at the time and who were also refugees of the Greek War of Independence that were brought to the United States.

At the Mount Pleasant Classical Institute (1830-1832), Christos Evangelides studied under the eminent Evangelinus Apostolides Sophocles. On October 28, 1832 – according to his diary – Christos returned to New York and attended the University of the City of New York (present-day New York University), where he founded a students' association named "The Philomathian Society", and finally, under the patronage of Samuel Ward, he attended Columbia College graduating October 4, 1836 (In the early 1850's, Columbia University conferred an honorary Masters degree by Columbia University).

In New York, Christos moved in the circles of prominent Philhellenes and Abolitionists such as William Cullen Bryant and the poetess Julia Ward Howe (who became the wife of Samuel Gridley Howe). The young Christos inspired William Cullen Bryant's poem "The Greek Boy," as well as the portrait by Robert Weir which accompanied Bryant's poem. He became the adopted brother of Julia Ward Howe (Chicago Post, 1897).

Christos Evangelides came to the United States seeking an American education and a better life, always with the intention of returning to Greece. His mother and sister both survived the Greek War of Independence. In 1836, he returned to Greece, and in 1837 settled in the port city of Hermoupolis on the island of Syros. Once in Greece, Christos Evangeles adopted the name Christos Evangelides. By 1842, he has married Catherine a young lady from Chios. Their children were Alexander, Calliope and Elene. In his diary, Christos records that his daughter Elene was born on May 11, 1856, but in a subsequent entry (September 1859) states that his family consisted of two children – Alexander and Calliope – and his wife, Catherine.

Among his accomplishments: Evangelides served as the President of the University of Athens; served as American Vice Consul in Athens and Syros. He was considered one of the great scholars of the United States and Europe. He brought to Syros the American idea of the value of real estate, by which he became wealthy. Evangelides was convinced of Syra's inevitable growth and invested in tracts of land in the immediate neighborhood of the then small town. Real estate investment and speculation was novel and beyond the comprehension of his fellow Greeks at the time. Christos Evangelides soon began to realize handsome gains from his real estate investments and soon became an esteemed man of wealth. His neighbors thereafter dubbed him the "Greek Yankee."

Christos Evangelides founded his school in 1846. Very soon his Lyceum school garnered accolades in Greece as well as from Philhellenes and the Greek diaspora. In addition to Greek teachers, foreigners taught at the Lyceum. The principles of the Lyceum were deeply rooted in Protestant missionary principles – the institution was based on "Love, Truth, Industriousness and repentance for sin" and its goal was the formation of a man "who has been taught not to expect anything in this world either of his parents or of the Government, except only of God and of himself". He instituted educational innovations, based on the American educational system at the time. In addition to traditional courses taught at the time, the school physical education, hygiene, foreign language, instrumental music, vocal music and dancing courses. He also introduced extra-curricular activities such as school plays, field trips, and their school newspaper H Melissa (The Bee).

Evangelides also travelled back to the United States asking for the help of philhellene Americans for to aid Greece and the liberation of Thessaly and Epirus (1854). He also travelled to London. Evangelides often showed up to Philhellenic events wearing a foustanela bringing with him Lord Byron's sword.

In 1877 Christos Evangelides opened another Lyceum in Athens, and died in that city in 1881.

"The Greek Boy"

Christos Evangelides was the inspiration behind American romantic poet William Cullen Bryant's "The Greek Boy" (1828) and Robert W. Weir's portrait painting which accompanied William Cullen Bryant's poem published in the Talisman.

[Christos Evangelides] attracted the attention of [William Cullen Bryant and Robert W. Weir] not only because he had rich and influential friends, but because he stood out for his Hellenism and wished everyone he came into contact with to realize that they ancient Greeks they so admired lived on in the modern Greeks, of whom he was a sterling example … Most New Yorkers had never met a Greek, although many had read about the ancient ones and the modern revolutionaries. … [Christos Evangelides] was an immigrant who did not try to assimilate. He wore his ethnic identity like a badge of honor.

Constantine G. Hatzidimitriou

"The Greek Boy"

Asher B. Durand's engraving of Robert W. Weir's portrait painting

The Greek Boy

Gone are the glorious Greeks of old,

Glorious in mien and mind;

Their bones are mingled with the mould,

Their dust is on the wind;

The forms they hewed from living stone

Survive the waste of years, alone,

And, scattered with their ashes, show

What greatness perished long ago.

Yet fresh the myrtles there-the springs

Gush brightly as of yore;

Flowers blossom from the dust of kings,

As many an age before.

There nature moulds as nobly now,

As e'er of old, the human brow;

And copies still the martial form

That braved Plataea's battle storm.

Boy! thy first looks were taught to seek

Their heaven in Hellas' skies:

Her airs have tinged thy dusky cheek,

Her sunshine lit thine eyes;

Thine ears have drunk the woodland strains

Heard by old poets, and thy veins

Swell with the blood of demigods,

That slumber in thy country's sods.

Now is thy nation free-though late

Thy elder brethren broke

Broke, were thy spirit felt its weight,

The intolerable yoke.

And Greece, decayed, dethroned, doth see

Her youth renewed in such as thee:

A shoot of that old vine that made

The nations silent in its shade.

In 1828, Samuel Finley Breese Morse accomplished painter and inventor of the telegraph and Morse Code also responded to the appeal of the Greek War of Independence. In that year Morse painted his version of the "The Greek Boy," its subject a youthful survivor of the Massacre of Chios who had been ransomed from the Turks by a group of Americans and sent to this country for adoption. The boy, Christos Evangelides, arrived in New York in 1828 and was a great attraction in literary and artistic circles. Morse painted his portrait in full costume, with Greek and Turk warriors struggling in the background (Soby, James Thrall Soby and Dorothy Canning Miller. Romantic Painting in America. Museum of Modern Art, 1943, p. 14)

Christos Evangelides sent the following letter dated July 25, 1875 from Syros to William Cullen Bryant:

Dear, Good Man, And Much-Beloved Mr. Bryant:

I have no words in which to express my gratitude to you for the good you have done to Greece and to "The Greek Boy." I owe to the Americans and to you my education and present happiness. My country is free and I am free, and what is more, I am a believer in Christ, thanks to those who taught me. I tried to make the best use of the talent I received from our Heavenly Father through the American schools and the examples of their noble men. My remaining days are few; I am trying to spend them in the service of my Redeemer by doing all the good that I know and can do. It is not likely that we shall ever meet on earth: let us meet in heaven. I am the old man now who was once "The Greek boy," and have the pleasure to be your grateful and sincere friend.

"The Greek Yankee"

Rev. William S. Balch, of New York, now traveling in the Holy Land, met at Syra,in the Archipelago, a Greek, educated in this country, of whom he says : "We called on Mr. Evangelides, the American Consul, a Greek – a Macedonian by birth, but an American by education and spirit. A more congenial spirit I have not met in many days. He has a large soul, and cherishes broad and liberal views of human rights, responsibilities and duties. He is a true man. I little expected to meet his like in this quarter of the globe.

By him I was introduced to General Bozaris, the brother of the lamented Marco Bozaris, immortalized in this country by his noble heroism in the cause of liberty, and in ours by the requiem of Fitz Grepne Haileck. This man bore his dead brother from the field of slaughter, and then returned to fight wiih redoubled ardor the battles of his country. He is a fine, venerable old man, still holding the office of General, and serving as a senator in his country. He is poor in this world's goods, has the care of a large family – of his own and his brother's – but wavers not in his love of freedom, and his admiration of our own great Washington.

Source: "The Greek Yankee." The Baltimore Sun, 15 January 1853, p. 5)

"The Super-Patriot"

Despite the support of all the devoted American Philhellenes, Christos Evangelides realized early on that not all Americans were Philhellenes and their perception of the Greeks of the time was was not positive. Evangelides "viewed it as his sacred duty to defend his country and people" against the "mishellenists." (Hatzidimitriou, Constantine G.)

Speech Given at Columbia College (June 25, 1835)

One of the many stigmas aduced against the character of of the Greeks in order to substantiate the argument that they degenerated from the noble spirit of their forefathers I beg leafe – and of you my fellow students to notice some of them now. The attempt to exculpate the Greeks from these through and through. I would consider it as insolence to the throne of Sacred Truth. Yet by bringing them once more before you and exhibiting them in the light in which they should have been you will be so far from condemning the Greeks that on the contrary you will regard these accusers as knaves, disobedient to justice – and in whose breasts sympathy never found shelter. As in all other trials in search of truth the Ring leaders are raised to the most conspicuous stations by dint of merit. So will I in this present occasion, like a good citizen submit to the existing custom and forthwith will introduce before you those three who most distinguished in leading the … mishellenes. You see that their number is a complete trio and having three given points we can at pleasure point out the center of the circle.

The first of these who lead the van is the mighty Sir William Gell – who having visited Greece and Turkey in 1805 published his travels in 1823 as "The present state of Greece." In addition to the unbecoming base and vilianous epithates with which he adorns the Greeks. He predicts some bitter callamaties against us but now being too late by 12 years for the fulfillment of the same. We begin to entertain some doubts but that he might have been inspired form the wrong quarters.

W.H. Humphreys comes next – of manly form, but childish brains – and as one of these scrims, bites, knocks and kicks when the puss makes way with its ginger cake – so he mourned and cursed the Greeks and more our noble prince Ypsilantis with word like these – I left my home with all its comforts and came to assist these wretches – and they have not appointed me to office – not withstanding my frequent aplications, I am weary, I am tired – I will no longer stay – I shall return as soon as the campaign is over. But he said it in such a ridiculous tone that the Greek maidens brooke their zones laughing.

Next comes the third – whose name unknown to most and forever so let be – for he was the bitterest sting to my Beloved Greece. He wrote a full octavo bearing facts such as a person out of the Lunatic asylum ever met with besides himself. Yes, in spite of your teeth he will insist that you have none. He will tell you that the Turkish women are better off shut up in the Harems than the Americans – and that there are more hogs in the streets of New York than there are dogs in Constantinople. But away with the Epicurean fellow and his pretty looking octavo. Not a drum nor a funeral note shall disturb it for we shall ascribe it to decay with all its profit and glory.

The boastful watchword of these Harpies has been "O! the degenerate Greeks ndash; O! the Piratical Greeks." That the Greeks have degenerated from the Spirit of their fathers they have only asserted but never proved – and wat was the spirit of our fathers? Was it not that which breathed upon the foe at Marathon Plataea – Thermoplyale and Salamis? And in these last days in the bloody cruel war – while famine, discord and death ravaged within, without friends or aid from abroad, and without the necessary engines of war – carried on by their sons – against one of the most powerful and vindictive nations in the world. Does spirit like this indicate degeneracy of the Greeks. But away with such men. Sympathy never found a drope of cold water in their breasts.

Lastly – no man who believes in the existance of an Almighty, merciful and just God would have ever dared exclaim that the Greeks are a Piratical nation. The Greek never became a pirate for plunder – neither would he shed the blood of a man. If the Greek became a pirate, it was necessity stronger than death that made hime one. If the Greek became a pirate – it was because he would not be a slave.

Were I myself in the same situation I would gladly turn a pirate, so would you and everybody else save these our accusers – for piracy too is too noble did for them. They would sooner be pick pockets, thieves, slanderers, villians, and cut throats. But away with men like these, for evil communication corrupts good manners.

Delivered June 25, 1835, Columbia College.

(Sourced from Hatzidimitriou, Constantine G.)

In subsequent returns to the United States his main goal was to secure aid and empathy for the Greek cause. Christos Evangelides would make public appearances and give lectures dressed in his foustanella and exhibiting various items from Greece including the sword of Lord Byron.

Lord Byron's Sword

Lord Byron's Sword was first brought to the United States from Greece in 1827, by Colonel Jonathan Miller who went to Greece in 1824 as

a volunteer in the Greek army, and after the siege and battle of Missolonghi, in April, 1826, returned to Vermont. He loaned

the sword to Christophorus Plato Castanis, a

Greek lecturer, who took the sword back to Greece and eventually Syros. In 1853, Christos Evangelides – United States

Consul at the time – recovered the sword and brought it back to the United States. Colonel Miller's daughter eventually

gained possession of the sword and donated it to the Vermont Historical Society.

(Sanborn, F.P. "Lord Byron in the Greek Revolution." Scribners' Magazine, Volume XXII, p. 357.)

In addition to public appearances and lectures, Evangelides would make his case via the American press.

Greece and America. An Appeal to the People of the United States

The following from Christos Evangelides entitled "Greece and America. An Appeal to the People of the United States" was published in the New York Herald on June 8, 1854 (page 8)

Free Citizens of the United States:

There is no other people to whom the [Greeks] under the yoke of the Mohamedans, to whom they can look up to for aid, than you. For four hundred years [the Greek] people have been groaning under the oppressive yoke of the Turk. They have been suffering what no other people have suffered. Eight generations have been swept away since their first oppressors, the Turks, invaded their country, destroyed their [churches], or turned them into mosques, cut off the tongues of a great many of their children, that they may forget the Greek language and Christian religion, deprived them of all the rights of citizens and of human beings, made ruzzias on the people of the country, and turned Into a wilderness what once was so fair and so rich.

Citizens of the United States – Peaceful habitations and flourishing villages have been swept away from the face of the earth by the Turks; wealthy and peat cities have been reduced to ruins and insignificance. The Turks, ever since they conquered these countries, liave been destroying what they have found; and they have built nothing – everything has been withering before them. Schools, education, the arts and sciences, commerce and political rights, have faded before them. Our country is desolate, and where the voice of prayer and thanksgiving were once heard, we now hear but the cry of the owl and jackall. These are facts knows to all of us. Visit Naousa, Beroca, and Cassandra, in Macedonia, aud you will see the stones and the ruins stained, and if you inquire of the people how they became so stained, you will be answered that they were stained by the blood of the myriads of children, women, aud old men that were butchered by Abouloubut, Pasha or the city or Theisalonica. Yes, dear Americans, I saw with my own eyes the ears of thousands of Greeks cut off and brought in baskets into the city of Thessalonica, into the house of the Pasha; and with my own eyes I saw loads of men's heads brought and exposed in piles before the Pasha and his people. Visit Ipsara aud Sclo, and you will see the ruins dyed with blood, and you will see the marble floor of the churches, to the present day, marked by the bloody impressions ot the bodies slain that died on that spot.

Americans! Happy people! Sons ol Washington aud Franklin – thirteen million immortal souls sent me here to call upon you for sympathy and help. They want your assistance – tbey need your help. It is enough, they cry – four hundred years of slavery is enough to suffer, aud we cannot suffer longer. They call upon you, Americans, to turn your sympathizing eyes upon them. You have assisted our brethren, the Greeks, that are now free – assist us now. It was we that fought the battles of the revolution of 1821. Ou: fathers bled – our old men were massacred – our mothers, and sisters, and brothers, have been led into captivity.

Americans, the person who addresses you now, in the name of thirteen million Christian Greeks, is the only one of a laree family of Macedonia that is alive, having been saved from the Turks by American citizens. Yes, Americans! it was the noble sons of America that snatched me from worse than death, and brought me to New York, and educated me, and taught me truth and liberty. It was P.H. Vandervoort, R.E. Glover, J. Whiting, and Daniel Jeptson, who brought me to the land of the free. You all received me then, and all blessed me, and tried to enlighten me and make me happy. For a poor orphan Greek boy you felt compassion; you did for him more than a father could do; and now that he comes before you as the representative of thirteen million ot his suffering fellow countrymen, longing for the blessings which you enjoy, and which have been taught to them by him whom you taught and blessed, and whom yon charged to do to his countrymen what you had done for him, will you not give ear to his humble voice? What! for a poor Greek boy to feel compassion, and not for a whole race of men ? I know the Americans are too noble. I know you will not abandon a brave people. Oh, you are too noble; you will do good to my country. It is lawful to do good. It is our duty to do good.

When the men of Macedonia invited by night, St. Paul, he went over to them and preached to them the Gospel. Now, the men of Macedonia have sent me to entreat you, in the name of everything that is dear and holy, to assist them in the defence of the pure doctrine which St. Paul preached. The same Macedonians are calling on you to come over and help them. We have called upon the Christians of Europe, but they heard us not; they have suited with the oppresors of our race; England and France fight aguint us; English and French officers, dressed in Turkish uniforms, lead the armies of the Turks against us; English aud French men of war carry provisions to our enemies and accompany their fleet against us; French and English men of war visit our ports, threatening us that they will hang us from the mast if we fight against the Turks. They have destroyed seventeen villages in Paromythia, and slain all the children, the old, and the feeble. An English agent, under the name of American, or Christian, philanthropist, went about, in the midst of our people, expressing his compassion for them, and for the success of liberty. He noted the names or all that sympathisingly opened their feelings to him, aud gave a list to the Pacha, who punished all these people.

Americans – our wrongs are greats – more than flesh and blood can bear. We asked for aid from the free Greeks; contributions were made, assistance was sent, but before it could reach our brothers in the field, the Christians of France captured the vessel; and, Oh heaven, the offerings of the poor for the distressed were thrown overboard. Yes, Americans, it is true, they did so; and when the news reached the ears of the people they wept, but the English and the French and the Turkish consuls laughed them to scorn. Americans, again, it is more than we can bear. Do not believe what they write in the English and Fench newspapers about Russian gold and Russian intrigues. Whenever the Greeks do not become blind organs to the wishes of England aud France, they accuse them of being paid by the Russians. The Greeks are good only when they do what the interests of England and France demand. But if the Greeks act for the interests or their own country, they are paid by Russia; they are the tools of Russia; Russian gold and Russian intrigue are said to have been the cause of all that does not please the Western Powers.

Americans, we ordered 8,000 muskets from Antwerp to be sent to ns. We paid for them, but the English captured and carried them to Malta.

I am a free citizen of the United States. When a little boy I was brought here. I was educated in Mount Pleasant Classical Institution, at Amherst, Massachusetts. I graduated in Columbia College. I can never be a friend to despotism. I am no Russian; but unfortunately so it is, Russia has shown more Christian feeling than England and France in this affair. The Greeks and all my countrymen are not Russian, but they ought to sympathise with any one that will sympathise with them. The Western powers are forcing them to become attached to the Russian. But they wish to be free, and one kind smile from America will be enough. Americans, if annexation be too much for this brave people to expect, whatever you do will be thankinlly received. You Americans have opened schools in Greece – you breathed in our hearts the spirit of liberty – you have planted the tree of liberty: now support it.

The English and French papers have been misrepresenting us. We wrote and forwarded refutations, but they refused publishing them in their papers.

If the object of the English and French is to curb the power of Russia, and keep the integrity or Turkey, why do they not do what the Christians have proposed? There are 12,000,000 of Christians and 3,000,000 of Turks. The Greeks are willing to have the Turks lire with them as fellow-citizens. They ask tor equality and laws, and religious toleration – to separate Church from the State – and to be governed constitutionally. Then there will be no cause for Russia to interfere; and in case she does there will be a population of 15,000,000 to defend their country; and then in case of them being too weak defend themselves against Russia, it will be easier for the Western Powers, to assist a nation of 15,000,000 in perfect agreement with themselves.

Americans! read the epistles of Anglicanus, written by an Englishmen. But rather than believe what English and French newspapers say, send a committee of American citizens into Greece and we will abide by their decision. Americans! I have been trying to do what you have taught me – my duty I have done, and am trying to to do all I can. I have sacrificed all. I am now pleading the cause of the oppressed. If I succeed we shall all rejoice. If not I have done all I can do. We may plant and water, but God must give the increase. To that great Being I surrender the cause of my injured country, and may He enlighten our hearts and understandings to do what is right. Americans, my last word is, remember that the 13,000,000 of people of whom I represent, and whose cause I am pleading, are of flesh and blood like you, and that they are in the greatest need.

Reunions in Greece

On April 14, 1853, at the Greek island of Syros, William Cullen Bryant was reunited with Christos Evangelides, the American consul in Syros at the time. William Cullen Bryant's letter:

On our voyage from Constantinople to Athens, the steamer stopped for some time in the port of Syra, where we began a quarantine of twenty-four hours. I wrote a note to the American consul, Mr. Evangelides, [born in Thessaloniki], educated in America, who came alongside of our steamer, and with whom we had a most interesting conversation.

"I am satisfied," said [Evangelides], "with regard to Greece. Her people are making the greatest sacrifices to acquire knowledge, and when this is the case, I expect everything. You see our town: those houses on the conical hill are Syra proper, those which cover the shore at its base form another city called Hermopolis. The place was a little village in the time of the Greek revolution; it has now a population of twenty thousand. Of these, three thousand are pupils in the different schools. In my own school are thirty-one boarders, of whom seventeen pay for their board and instruction; the rest are poor boys. In twenty years it will be hardly possible to find a Greek who cannot read.

On June 17, 1867, Julia Ward (Julia Ward Howe) now 48 years old was met by Christos Evangelides – her childhood friend "Christy", the Greek boy befriended by her father, Samuel Ward. Her journal says:

He was now a prosperous man in middle life, full of affectionate remembrance of the family …, and of gratitude to [her father] 'dear Mr. Ward.' He welcomed her most cordially, and introduced her not only to the beauties of Syra, but to its principal inhabitants, the governor of the Cyclades, the archbishop, and Doctor Hahn, the scientist and antiquary.

(Richards, Laura E. and Elliott, Maud Howe. "Julia Ward Howe, 1819-1910." Houghton Mifflin Company, 1915, p. 141)

Towards the end of his life, Evangelides wrote to his friend and famous American poet William Cullen Bryant: "You must know that I persist in my adoptive country and I am proud to be a Yankee. I belong to the Empire state, I am a New Yorker … When Americans find their way to Syros, it is for me a day of relief and joy".

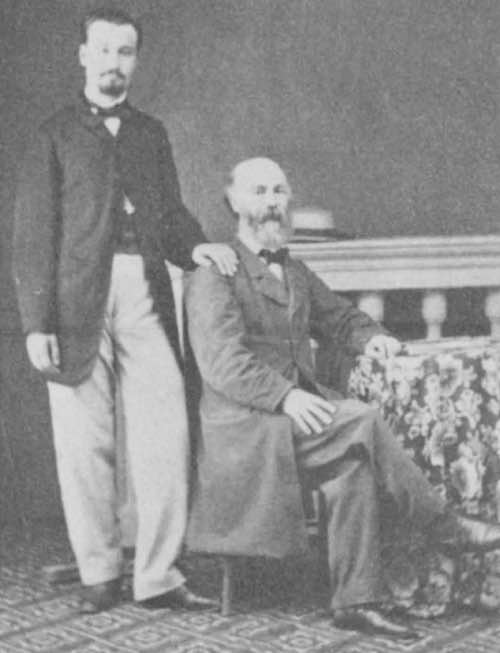

Alexander C. Evangelides

Christos Evangelides and his son Alexander

Alexander C. Evangelides, the eldest son of Christos Evangelides, was born in Athens in 1847. Little is known of Alexander’s early life in Greece, but by 1863 he was living in Alexandria, Egypt. His father had maintained his contacts with his friends in New York and the Protestant missionaries and was able to send his son to be educated in the United States as well. Alexander was under the tutelage of his prominent father's friends – William Cullen Bryant, Wendell Phillips and Henry Ward Beecher. Like his father, Alexander was also a Columbia University graduate.

In 1867 he returned to the United States, where he passed his consular examination and began work in the New York Customs House. In 1870, he was appointed United States Vice Consul to Egypt. Having fallen out with the consul, George Butler, he left Alexandria, Egypt and the foreign service in 1871 and returned the United States.

He worked for the Civil Service Commission in Brooklyn, and in the late 1880s was chief clerk in the bureau of construction in the Navy Yard. Alexander became a prominent journalist, editor of the Brooklyn Citizen and Brooklyn Eagle newspapers, a member of the Brooklyn City Council, and secretary of the Brooklyn Mayor's office.

He was also a lecturer and published "Shall Greek be Taught as a Living Language" ("Greek as a Living Language") Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 21 January 1896, p. 5).

Alexandros C. Evangelides passed away on December 26, 1905.

Bibliography

Hatzidimitriou Constantine G. "Christodoulos M.L. [Evangeles] Evangelides (1815-1881): An Early Greek American Educator and Lobbyist." Journal of Modern Hellenism, vols. 21-22, 2004-2005, pp. 205-238

Bryant ΙΙ, William Cullen. The Letters of William Cullen Bryant. Fordham University Press, 1883, vol. 3, pp. 280, 292

Bryant ΙΙ, William Cullen. The Poetical Works of William Cullen Bryant, edited by Parke Godwin. New York: Appleton, 1883.

Hannoosh, Michèle. "Practices of Photography: Circulation and Mobility in the Nineteenth-Century Mediterranean." History of Photography, 2016, 40:1, 3-27.

Gregoriadis, John. "The Greek Boy." Modern Greek Studies Yearbook [University of Minnesota], vols. 10-11, 1994 - 1995, pp. 603 - 628.

Larrabee, S.A. Hellas Observed: The American Experience of Greece 1775-1865. New York, New York University Press, 1957, p. 267.