History of the Order of AHEPA 1922 - 1972

Part I - The First Greeks in the New World

Page 3

DIASPORA

The history of the Greek people is one of "Diaspora " – dispersion -- throughout the world from 500 B.C. to the present day.

In the days of Pericles, the Greeks left their homeland to found new colonies throughout the Mediterranean Sea and its borders, into North Africa, Asia Minor, and as far as India. Sprung from a land with limited resources of its own, and with the sea their second homeland, Greeks travelled to the far reaches of the world.

Wherever men were to be found for the past 2,500 years, there also were to be found the Greeks, if in limited numbers. Emigration from Greece has almost always been of an economic origin, except during the years of 1456, (when Athens fell to the Turkish invaders), to 1830, when Greece finally regained her independence from Turkey after almost 400 years of subjugation. In those 400 years, emigration was a means to escape Turkish rule and oppression.

This book will endeavor to portray this emigration, and to bring together some of the facts concerning the Greeks who settled in America.

Although the primary purpose of this book is to offer a history of the Order of Ahepa, the American Hellenic Educational Progressive Association, it will also describe the beginnings of Greek immigration to this country, as a prelude to the causes and purposes of the establishment of the Order of Ahepa in Atlanta, Ga., on July 26, 1922.

The following chronicle of early Greeks in the New World, (Part I), begins with the voyages of Columbus, and continues to the first major immigration of the 1890s. Part II will deal with the problems and circumstances of mass immigration to the United States, and Part III with the establishment of the Order of Ahepa, and its history, in chronological sequence.

Page 4

JOHAN GRIEGO (1492 A.D.)

Johan Griego, a Greek sailor from Genoa, was a member of the crew of Christopher Columbus. In his book "Christopher Columbus, His Life, His Work, His Remains as Revealed by Original Printed and Manuscript Records," author John Boyd Thacher mentions this sailor. The words "Griego - Grecque - Greco" were quite common in early Spanish and French writings, and always denoted a Greek.

THEODOROS - A GREEK SAILOR (1528 A.D.)

Don Pamphilo de Narvaeth was commissioned by the King of Spain to explore the Gulf of Mexico and the coasts of Florida. He departed from Spain on June 17, 1527 and reached the area near what is now Tampa, Fla. on April 14, 1528. The ships were battered by storms, and repairs to the hulls were needed. A Greek sailor on the expedition, "Don Teodoro," made the repairs to the ship hulls which he caulked with palmetto oakum and tarred with pitch, made from pine trees. Teodoro, or Theodoros, followed a trade practiced by Greek fishermen for many centuries, in making the repairs.

The expedition continued northward, and when near what is now Pensacola Bay, in October, 1528, stopped to secure fresh water. Narvaeth reached an agreement with Indians on shore for fresh water in exchange for gifts, but the Indians insisted on hostages. "Theodoros offered to go ashore, and he was accompanied by a Negro from the crew; in turn, the Indians left two of their own as hostages with the Spaniards."

"Neither Theodoros nor the Negro were ever seen again, and the ships sailed without them."

There is a sequel to the story. Twelve years later in October, 1540, explorer De Soto landed at an area then known as Mauvilla, which must have been near Mobile, Alabama. While there, he learned that a "Christian, or white man, by the name of Theodoros, had lived in the vicinity with the Indians" since the time of Narvaeth's visit in 1528, twelve years earlier. This history then relates that the Indians showed De Soto a dagger that had belonged to Theodoros. Also, on October 13, 1540, De Soto and his men passed through an Indian village called Piachi, and they were told by the villagers that "Indians had killed Theodoros, and the Negro who was with him."

From the above, it would seem evident that the first Greek to set foot on American soil was this Greek sailor, Theodoros, in October, 1528.

NIKOLAO, IOANNI, & MATTHEO (1520 A.D.)

Spanish and English historians mention three Greeks who were with Ferdinand Magellan in 1520 on his voyage to Patagonia. Their names are only listed as: Nikolao, loanni, and Mattheo.

Page 5

PETROS THE CRETAN (1535 A.D.)

Petros the Cretan, a Greek adventurer and soldier, was known as Pedro Di Candia by the Spanish. He was a lieutenant of Francisco Pizzaro (1470-1541) who conquered the empire of Peru and founded the city of Lima, as the capital of Peru in 1535. Petros the Cretan lived an adventurous life as a part of Pizzaro 's expeditions and forces, and was killed in 1542, the year following Pizzaro's assassination in Peru.

IOANNIS and GEORGIO (1578 A.D.)

When Sir Francis Drake reached Valparaiso, Chile in 1578 he found there a Greek pilot, whose name was Ioannis. loannis acted as Drake's pilot as far as Lima, Peru.

Ten years later, Englishman Thomas Cavendish met a Greek pilot by the name of Georgio, who knew the waters of Chile.

Both of these Greek pilots must have been in the area for many years in order to have sufficient knowledge of the waters to act as pilots for visiting ships.

JUAN de FUCA (Apostolo Valeriano) (1592 A.D.)

The Juan de Fuca Straits

The Strait of Juan de Fuca was discovered in 1592 by Juan de Fuca, born Apostolo Valeriano on the island of Cephalonia, Greece. The Strait is some 60 miles in length, and separates the northwestern edge of the state of Washington from Vancouver Island, to the north. It leads into Puget Sound, to the south, and into the Georgia Strait, to the north, from the Pacific Ocean.

Although discovered in 1592 by this Greek ship captain, it was not until 1725 that the Russian Academy gave the name "Juan de Fuca Straits" to this open passage from the Pacific Ocean, which Juan de Fuca had thought was the western terminus of the long-sought Northwest Passage.

The story of Juan de Fuca, born Apostolo Valeriano in Cephalonia, concerns the frustrating search for the Northwest Passage through America, from Europe to Asia, which explorers from England, Spain, and France sought for many years without success.

Juan de Fuca was a ship captain who worked for some 40 years in the Spanish West Indies for. Spain. Spain ruled Mexico, and in 1592 Juan de Fuca was commissioned by the vice premier of Mexico to seek the Northwest Passage, from the Pacific side of the continent. With one ship, he set sail north along the Pacific coast, and he entered a gulf or opening at 48° Latitude North, which he explored for 20 days. He noted that the land was sometimes Northwest and sometimes Northeast, and that the sea was much deeper close to the opening of the gulf.

Page 6

He stated that at different places on shore he saw people, who wore animal skins for clothing, and that there was evidence of gold and silver. Feeling that he had discovered the Passage, he returned to Acapulco with his report, and with the hope of being rewarded for his services. He received nothing for his efforts, and two years later left for Spain, where he presented himself before the King, where he received a warm welcome, but no rich rewards. He left for Italy, on the way to his home in Cephalonia, Greece.

In Italy, he met Michael Lok, an Englishman who was Consul of England at Halepi, Syria. They met at Venice, where Lok had stopped en route home to England, and Juan de Fuca related his experiences to Lok. He also offered to go England with Lok, and to work for England to find the Northwest Passage to Asia, if the Queen would give him a ship of 40 tons. Although Lok wrote to England to secure further help and assistance for such a venture, nothing came of the request. Juan de Fuca then left for Cephalonia, where he died about 1601.

The story of Juan de Fuca was told by Michael Lok, and it was printed in "Purchas' Pilgrimes," a collection of voyages by explorers, in 1625.

In his book "Names on the Land: A Historical Account of Place-Naming in the United States" author George R. Stewart describes the Pacific Coast northward from San Francisco Bay as a "dangerous coast, always a lee shore against the westerly gales sweeping across the open ocean. The surf crashed at the foot of cliffs, and the fog shut down close, day after day. So, even when a shipmaster ventured there, he kept good offing, and saw only a few dim headlands, and found no harbors. It remained a region of mystery, where some men still hoped to find the Northwest Passage."

The explorers of the 16th, 17th, and 18th century failed to find the open passage from the Pacific Ocean that Juan de Fuca had discovered in 1592, and treated the story as a myth, until 1792 when Captain George Vancouver entered the passage, which he called skeptically "the supposed straits of de Fuca" as he entered them. Although the straits were not the Northwest Passage, as Juan de Fuca had believed, his story about the discovery was thus finally verified after almost two centuries had passed.

Although many historians disputed the story of Juan de Fuca, since Spanish and Mexican records of the day made no mention of this Greek captain, Alex S. Taylor set out to prove in Sept. 1859 in "Hutchings California Magazine" that such a man did exist, and he pointed out that the Spanish and Mexicans had destroyed the records. Taylor contacted the American consul in Zakintho, Greece, A. S. York for family records of de Fuca. In the records sent to Taylor was a letter of Count Metaxa, from Argostoli, who assured him that in 1854 in the village of Mavrata of Cephalonia there were three old men, 80 years of age, who assured him that their ancestors were of the family of Fuca. There was also a copy of a record of the autocrat of Byzantine, Alexiou tou Komninou Porfiroyennitou, addressed to those who resided in Herakleion, Crete, dated in 1182, in which the name "Fokas" was one of those prominent in Constantinople autocracy.

Page 7

Also included was the genealogy of Georgios Fokas, from Argostoli, Cephalonia, as well as a biography of Juan de Fuca, taken from the book of a priest, A. Mazaraki, which he had written in Venice in 1843, entitled "Lives of Famous Cephalonians." Mazaraki wrote that two brothers by the name of Fokas had left Constantinople in the 15th century. One brother, Andronikos, settled in the Peleponnesus of Greece, and the other brother, Emmanuel, went to Cephalonia. Emmanuel Fokas raised several sons, Stephano, Emmanuel, Hector, Iakovos, Jacob, and Ioannis, or John. Ioannis, or John, was given the nickname of "Valerianos" since the family lived in the village of that name. The village of Mavrata, where Count Metaxa found the descendants of Juan de Fuca, and also where U.S. Consul York found several people with the name of "Fokas" is located very close to the village of Valeria nos.

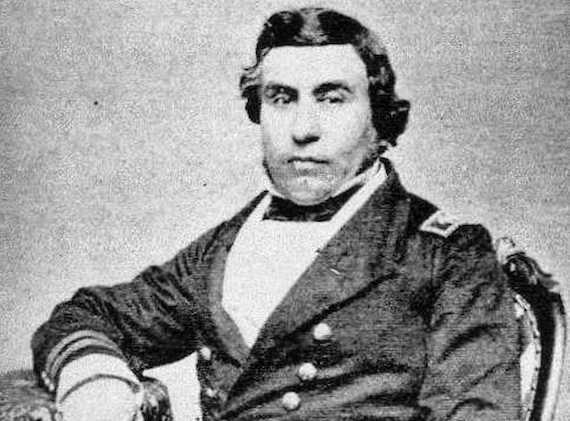

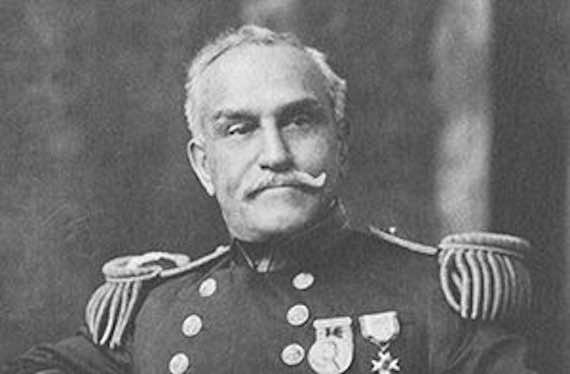

Between 1840 and 1846, the discussion of the discovery of the Straits of Juan de Fuca came into prominence because of the differences between England and America over the boundaries of the Oregon Territory, and the Treaty of Washington of June 15, 1846. America sent ship captain Charles Wilkes in June, 1842 to find the boundaries of the territory. The voyage that Wilkes made was written by George Mousalas Colvocoressis, an officer in the U.S. Navy, who was born in Greece, and who had a distinguished career himself in the Navy.

MICHAEL URY OF MARYLAND (1725)

In 1725, the Maryland General Assembly adopted a legislative act entitled "An Act for the Naturalization of Michael Ury of Prince Georges Couniy, a Greek, and his Children now Residents in this Province."

Michael Ury became a naturalized citizen, by act of the General Assembly of Maryland, some 50 years before the American Revolution. Apparently Ury could not write English, for his Will is signed with a mark, and his name filled in by someone else who spelled the name "Michel Youri." In Maryland records, the name is also spelled "Urie" and "Urion."

The earliest reference to Michael Ury in Maryland records is dated June, 1724. He died in 1752, and his Will was probated September 28, 1751. He left all of his property to his wife, Margaret, which included a tract of land called "Smyrna." His wife Margaret died some years later, her will being probated on Oct. 31, 1768.

Page 8

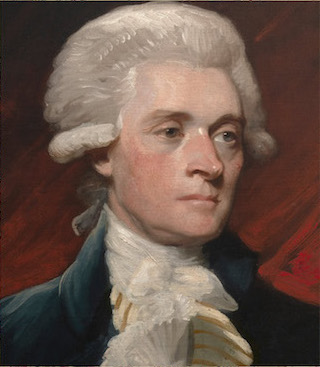

JOHN PARADISE OF WILLIAMSBURG, VIRGINIA

John Paradise was a linguist and learned Greek scholar, who lived in both England and France where he became a close acquaintance and friend of Benjamin Franklin. He was a protege of Franklin and Thomas Jefferson, and one of the close circle of friends of Samuel Johnson of England. He met Lucy Ludwell, of one of Virginia's first families, in England, where they were married.

He became a naturalized citizen of America, and their home, the Ludwell - Paradise House, was the first of the homes restored in Williamsburg, Va., and is considered one of the finest examples of early American homes.

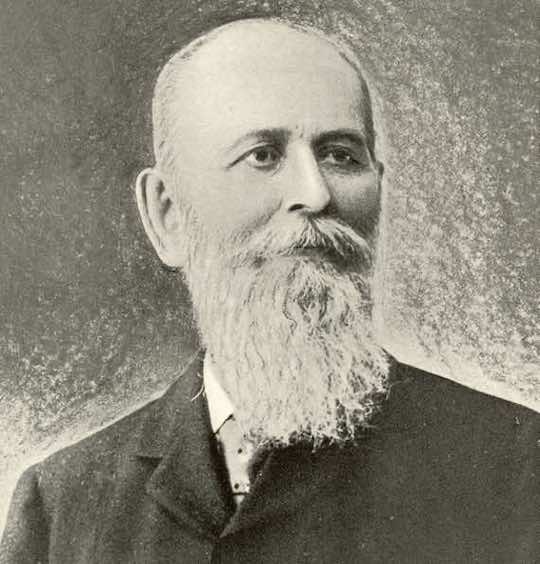

John Paradise

Courtesy: John Paradise: The First Naturalized U.S. Citizen and Thomas Jefferson's Greek-Language Tutor

EUSTRATE IVANOVICH DELAROF (1783)

Alaska was discovered by Captain Vitus Bering, a Danish explorer working for the Russians, during his two voyages of 1728 and 1741. During his first voyage he discovered the strait which separates Asia and North America, named after him as Bering Strait. Thereafter, there were many expeditions to the North American coast from Russia, and one was commanded by Eustrate lvanovich Delarof, a native of the Peleponnesus of Greece, who was a factor in trading firms from Russia.

From 1783 until 1791, Delarof was in nominal charge of all Russian trading operations in the Aleutians and Alaska, where he had to resist the attempts of the English, French and the Spanish expeditions who also wanted to hunt the same land for sea-otters, sealions, and seal. Through his efforts, Russia maintained control of the area, and, subsequently, Alexander Baranov, known as the first Russian governor of Alaska, set up headquarters at New Archangel, near present Sitka, in 1799.

One of the twelve fortified stations established in Alaska by the Russians was named in honor of Delarof, and was known as Port Delarof.

NEW SMYRNA, FLORIDA (1768)

At the Peace of Paris in 1763, England exchanged newly acquired Havana, Cuba to Spain, for Florida, but when the English took over the new Florida territory, they found very few settlers. The Spanish settlers had all left for Cuba after the peace treaty. The English now faced the problem of colonizing their new land.

In his book "New Smyrna, An 18th century Greek Odyssey" Dr. E. P. Panagopoulos, Professor of History at San Jose State College in California, presents a full and absorbing history of the English attempt at colonizing Florida, the colony of "New Smyrna" on the East Coast of the state.

Page 9

After a study of the soil and climate of Florida, the English decided that the type of settlers needed should be those whose religion "will be a bar to their forming connections with the French or Spaniards; and who will readily intermarry and mix with our own people settled there." Archibald Menzies wrote that:

"The people I mean, are the Greeks of the Levant, accustomed to a hot climate and bred to the culture of the vine, olive, cotton, tobacco, etc., as also to the raising of silk; and who could supply our markets with all the commodities which at present we have from Turkey, and other parts. These people are in general, sober and industrious; and being reduced, by their severe masters, to the "reatest misery, would be easily persuaded to fly from slavery (from the Turks), to the protection of a free government. The Greeks of the islands would be the most useful, and the easiest to bring away, as they are more oppressed than any others, having the same taxes to pay as the Greeks of the continent; with the addition of an annual visit from the Capitan Pacha, or Turkish High Admiral. The sums arising from their exportation of vast quantities of silk, wine, oil, wheat, tobacco, mastick, cotton, hardly suffice to satisfy their greedy tyrants, who fleece them upon all occasions. It may be observed that they are excellent rowers, and might be of great service m the inland navigation of America."

lt was reported that besides the Greeks living in Greece, and in Asia ,1inor, that there were many Greeks settled in Minorca, and the Engli,-h felt that the Turkish rulers of Greece would not object if the English enticed Greeks to leave their homeland for a new country and, hopefully, a better life.

Dr. Andrew Turnbull, who was married to Maria Gracia Dura Biu, the daughter of a Greek merchant from Smyrna, Asia Minor, secured a grant of 40,000 acres of land in conjunction with Sir William Duncan, for the East Coast of Florida, with the requirement from the English government that it be settled within 10 years in the proportion of one person for every hundred acres. Turnbull sailed for America in 1765 and in St. Augustine, Florida, he secured the grant of land from Governor James Grant. The land grant was located about 75 miles south of St. Augustine, in what is now New Smyrna Beach, Florida. He then returned to England where he secured financing for his forthcoming venture through bounties from the government and the Board of Trade, and then, sailed for the Mediterranean to search for his colonists "for a Tract of Land in East Florida on which I might settle a small Colony of Greeks," as Turnbull explained in a letter to Lord Shelburne.

In June, 1767, Turnbull arrived with his ships in the Mediterranean, and he visited Minorca; Leghorn, Italy; Smyrna, Asia Minor; the island of Melos; Mani, Koroni, Greece; Methoni, Greece; Crete; Santorini; Corsica; Mahon. He found opposition from French, Italian, and Turkish authorities, who did not want to see their subjects leave, but after persistent efforts, he finally rounded up about 1,400 colonists and left for his new colony in East Florida, which he was to name "New Smyrna" in honor of his wife, a native of Smyrna, Asia Minor.

Page 10

Professor Panagopoulos' research on the New Smyrna Colony has brought to light many of the names of these first Greek colonists to the New World, such as: Gasper Papi, Anastasios Mavromatis, Demetrios Fundulakis, Maria Parta (or Ambross), Kyriakos Costas, loannis Giannopoulos, Kyriakos Exarhopoulos, Nicholas Stefanopoli, Petros Drimarachis, Petros Cosifachis, (Cotsifakis) Michael Costas, Elia Medici, Clatha Corona, Ioannis Koluminas, Domingo Costa, Maria Bross, Yorge Costa, Antonio Llambias, Marcos Andreu, Nicolas Salada, Domingo Exarcopoulos, Michael Costa.

Turnbull's fleet of eight ships with 1,403 colonists on board left Gibraltar on April 17, 1768 for the long voyage across the Atlantic to Florida. Although records are incomplete, at least 500 of these colonists were from the mainland and the islands of Greece, and the others were from Minorca, Italy, Corsica, and Mahon. Included among these latter were also a large number of Greeks whose families had emigrated in earlier years from Greece, to escape Turkish oppression. (There were more than 700 emigrant Greeks in Corsica, alone, at the time, who were from the Peleponnesus.)

During the long voyage, 148 died on board ship, and only 1,255 survived to reach Florida. They landed at St. Augustine, Fla., prior to making plans to proceed to the new colony located 75 miles south.

Originally, Turnbull had planned on a colony of only 500 for his new project, and during his earlier visit to St. Augustine, had laid plans for that number. He now arrived at St. Augustine on June 26, 1768 with almost three times that number. Provisions were insufficient, and the colonization was faced with almost unsurmountable difficulties from the beginning. Mosquitoes and malaria added to their misery after their arrival at New Smyrna, for the whole area was called "the Mosquitoes" and clouds of the insects swarmed everywhere. Food was short, sickness prevalent, and in 1768 the deaths amounted to 300 men and women, and 150 children, or a total of 450 dead out of the 1,255 who started the colony.

A quiet plan of 300 to escape by ship to Cuba was discovered, and they were turned back. Three of the ringleaders were executed for their plotting. After the rebellion, the work continued to raise crops and develop the land, but the deaths by stanation and sickness continued. Turnbull and his partners in England tried to raise more funds to continue the colony, for this was a commercial venture, intended to bring profits to its hackers.

During the life of the colony (1768-1777) 670 adults and 260 children died there -- a total of 964 deaths in nine years. Within only 24 months after the arrival of the 1,255 colonists in 1768, there were only 628 left alive; 627 had died within the first 24 months.

Although they had been promised "freedom" or discharge when they first embarked after serving their four or six years of service for Turnbull, things were going so badly for the colony's owners, that when the colonists did make application for discharge after serving their work time of several years, they were turned down and thrown into confinement. There was no way out for these unfortunate human beings, and most of them found death to be their only escape.

Page 11

Finally, after repeated petitions seeking freedom, and the conditions of New Smyrna had become an open scandal within British government circles and courts, all of the colonists were set free by Andrew Turnbull's attorneys. During May and June, 1777, most of the people of New Smyrna had migrated to St. Augustine, Fla., and New Smyrna remained deserted. Turnbull, his wife and children moved to Charleston, S.C., after being imprisoned in St. Augustine for debts to his creditors in England.

The British governor allotted lands between St. Augustine and the St. John's river for the New Smyrna colonists who survived, and this area was called the '"Greek Settlement." By January 15, 1778, there were still 419 men, women and children still alive, and 128 of these were children born in New Smyrna. The Greek, Minorcan, and Italian families intermarried, and their numbers increased to 460 in 1784.

The New Smyrna colonists mostly stayed in St. Augustine, although some did return to Europe, or went to other areas, and those that remained prospered, and held title to almost 49,000 acres of land after Florida became a State. Michael (Miguel) Costa was registered in 1783 as a "Medical Doctor." Ioannis Giannopoulos (Juan Janopoli) became first a carpenter, then a teacher, although he came to New Smyrna from Mani when only 18 years of age. An old wooden structure, the "oldest wooden schoolhouse in the United States" is pointed out to visitors today as the original Ioannis Giannopoulos schoolhouse, and a street is named after the Greek teacher.

Historians of the 18th and 19th century gave the following accounts of the New Smyrna Settlement (Romans):

"The situation of the town, or settlement, made by Dr. Turnbull, is called New Smyrna from the place of the doctor's lady's nativity. About fifteen hundred people, men, women, and children, were deluded away from their native country, vvhere they lived at home in the plentiful cornfields and vineyards of Greece and Italy, to this place, where, instead of plenty, they found want in the last degree; instead of promised fields, a dreary wilderness, instead of a grateful, fertile soil, a barren, arid sand, and in addition to their misery were obliged to indent themselves, their wives and children for many years to a man who had the most sanguine expectations of transplanting bawshawship (pashaslich) from the Levant. The better to effect his purpose, he granted them a pitiful portion of land for ten years upon the plan of feudal system. This being improved, and just rendered fit for cultivation, at the end of that term it again reverts to the original grantee may, if he chooses, began in a new state of vassalage for ten years more.

Page 12

Many were denied even such grants as these, and were obliged to work at tasks in the field. Their provisi0ns were, at the best of times, only a quart of maize per day, and two ounces of pork per week. This might have sufficed with the help of fish, which abounded in this lagoon, but they were denied the liberty of fishing, and, lest they should not labor enough, inhuman taskmasters were set over them and instead of allowing each family to do with their homely fare as they pleased they were forced to join all together in one mess, and at the beat of a vile drum to come to one common copper, from whence their hominy was ladled out to them; even this coarse and scanty meal was, through careless management, rendered still more coarse, and through the knavery of a providetor and pilfering of a hungry cook, still more scanty masters of vessels were forewarned from giving any of them a piece of bread or meat.

Imagine to yourself an African -- one of a class of men whose hearts are generally callous against the softer feelings -- melted with the wants of these wretches, giving them a piece of venison, of which he caught what he pleased, and for this charitable act disgraced and, in course of time, used so severely that the unusual servitude soon released him to a happier state.

Again, behold a man obliged to whip his own wife for pilfering bread to relieve his helpless family; then think of a time when the small allowance was reduced to half, and see some brave, generous seamen charitably sharing their own allowance with some of these wretches, the merciful tars suffering abuse for their generosity, and the miserable objects of their ill-timed pity undergoing bodily punishment for satisfying the cravings of a long-disappointed appetite, and you may form some judgment of the manner in which New Smyrna was settled. Before I leave this subject, I will relate the insurrection to which those unhappy people at New Smyrna were obliged to have recourse, and which the great ones styled rebellion. In the year of 1769, at a time when the unparalleled severities of their taskmasters, particularly one, Cutter, (who had been made a justice of the peace, with no other view than to enable him to execute his barbarities on a larger extent and with greater appearance of authority) had driven these wretches to despair, they resolved to escape to the Havannah.

To execute this they broke into the provision stores and seized on some craft lying in the harbor, but were prevented from taking others by the care of the masters. Destitute of any man fit for the important post of leader, their proceedings were all confused and an Italian of very bad principles, but of so much note that he had formerly been admitted to the overseers' table, assumed a kind of command. They thought themselves secure where they were and this occasioned a delay till a detachment of the ninth regiment had time to arrive, to whom they submitted, except one boatful, which escaped to the Florida Keys and were taken up by a Providence man.

Page 13

Many were the victims destined to punishment, as I was one of the grand jury which sat fifteen days on this business, I had an opportunity of canvassing it well, but the accusations were of so small account that we found only five bills; one of these was against a man for maiming the above said Cutter, whom it seems they had pitched upon as the principal object of their resentment, and curtailed his ears and two of his fingers, another for shooting a cow, which, being a capital crime in England, the law making it such was here extended to this province. The others were against the leader, and two more for the burglary committed on the provision stOregon The distress of the sufferers touched us so that we almost unanimously wished for some happy circumstances that might justify our rejecting all the bills, except that against the chief, who was a villain. One man was brought before us three or four times, and, at last, was joined in one accusation with the person who maimed Cutter; yet, no evidence of weight appearing against him, I had an opportunity to remark, by the appearance of some faces in court, that he had been marked, and that the grand jury disappointed the expectations of more than one great man.

Governor Grant pardoned two, and a third was obliged to be the executioner of the remaining two. On this occasion I saw one of the most moving scenes I ever experienced; long and obstinate was the struggle of this man's mind, who repeatedly called out that he chose to die rather than be the executioner of his friends in distress, this not a little perplexed Mr. Woolridge, the sheriff, till at length the entreaties of the victims themselves put an end to the conflict in his breast, by encouraging him to act.

Now we beheld a man thus compelled to mount the ladder, take leave of his friend in the most moving manner, kissing him the moment he committed them to an ignominious death. Cutter sometime after died in a lingering death, having experienced besides his wounds the terrors of a coward in power overtaken by vengeance."

Another historian, Dewhurst, continues this narrative and tells of the outcome of the difficulties between Turnbull and these Greek immigrants:

"After the suppression of this attempt to escape, these people continued to cultivate the land as before, and large crops of indigo were produced by their labor. Meantime the hardships and injustice practiced against them, continued until in 1776, nine years from their landing in Florida, their number had been reduced by sickness, exposure and cruel treatment from fourteen hundred to six hundred.

"At that time, it happened that some gentlemen visiting New Smyrna from St. Augustine were heard to remark that if these people knew their rights they never would submit to such treatment, and that the governor ought to protect them. This remark was noted by an intelligent boy who told it to his mother, upon whom it made such an impression that she could not cease to think and plan how, in some way, their conditions might be represented to the governor. Finally, she decided to call a council of the leading men among her people. They assembled soon after in the night, and devised a plan of reaching the governor.

Page 14

Three of the most resolute and competent of their number were selected to make the attempt to reach St. Augustine and lay before the governor a report of their condition. In order to account for their absence they asked to be given a long task, or an extra amount of work to be done in a specified time, and if they should complete the work in advance, the intervening time should be their own to go down the coast and catch turtle. This was granted to them as a special favor. Having finished their task by the assistance of their friends so as to have several days at their disposal, the three brave men, most worthy of rememberance, were Pellicieris, Llambias, and Genopley. Starting at night they reached and swam Motanzas inlet the next morning, and arrived at St. Augustine by sundown of the same day. After inquiry they decided to make a statement of their case to Mr. Young, the attorney-general of the province. No better man could have been selected to represent the cause of the oppressed. They made known to him their condition, the terms of the original contact, and the manner in which they had been treated. Mr. Young promised to present this case to the governor and assured them if their statements could be proved, the governor would at once release them from the indentures by which Turnbull claimed to control them. He advised them to return to Smyrna and bring to St. Augustine all who wished to leave New Smyrna and the service of Turnbull. The envoys returned with the glad tidings that their chains were broken and that protection awaited them. Turnbull was absent, but they feared the overseers, whose cruelty they dreaded.

They met in secret and chose for their leader Mr. Pellicieris, who was head carpenter. The women and children with old men were placed in the center and the stoutest men armed with wooden spears were placed in front and rear. In this order they set off, like the children of Israel, from a place that had proven an Egypt to them. So secretly had they conducted the transaction, that they proceeded some miles before the overseer discovered that the place was deserted. He rode after the fugitives and overtook them before they reached St. Augustine, where provisions were served out to them by order of the governor. Their case was tried before the judges, where they were honestly defended by their friend the attorney-general. Turnbull could show no cause for detaining them, and their freedom was fully established. Lands were offered them at New Smyrna, but they suspected some trick was on foot to get them into Turnbull's hands, and besides they detested the place where they had suffered so much. Lands were therefore assigned them in the north part of the city, (St. Augustine) where they have built houses and cultivated their gardens to this day. Some by industry have acquired large estates. They at this time form a respectable part of the population of the city."

Page 15

The same historian, in commenting upon the characteristics of these people, quotes, from Forbes' "Sketches, etc." published m New York in 1821, as follows:

"I am pleased to quote from an earlier account a very favorable, and, as I believe, a very just tribute to the worth of these Minorcan and Greek settlers and their children. Forbes, in his sketches, says: "They settled in St. Augustine, where their descendants form a numerous, industrious, and virtuous body of people, distinct alike from the indolent character of the Spaniards, who have visited the city since the exchange of flags. In their duty as small farmers, hunters, fishermen, and other laborious but useful occupations, they contribute more to the real stability of society than any other class of people; generally temperate in their mode of life and strict in their moral integrity, they do not yield the palm to the denizens of the land of steady habits. Crime is almost unknown among them; speaking their native tongue, they move about distinguished by a primitive simplicity, and purity as remarkable as their speech.'"

Dewhurst, continuing his own narrative, adds:

"Many of the older citizens now living remember the palmetto houses which used to stand in the northern part of the town, built by the people who came up from Smyrna. By their frugality and industry the descendants of those who settled in Smyrna have replaced these palmetto huts with comfortable cottages, and many among them have acquired considerable wealth, and taken rank along with the most respected and successful citizens of the town."

PEDRO SAMUEL SPIRO (1814)

[ Pedro Samuel Spiro was born on the island of Hydra, Greece, in the late 18th century. With his brother Miguel Teodoro Spiro he emigrated to the city of Buenos Aires. ]

Pedro Samuel Spiro was a young Greek who commanded the small riverboat Carmen in Argentina at the battle of Martin Garcia early in 1814, as part of the fleet of Admiral Guillermo Brown. Later that year, when Brown's forces attacked the Spanish fleet at Arroyo de la China, the Carmen grounded under heavy enemy fire. Spiro disembarked his crew and blew up his ship and himself to avoid capture. Argentina issued a Navy Day stamp in 1971 picturing this historic warship, commemorating the action of Pedro Samuel Spiro.

Page 16

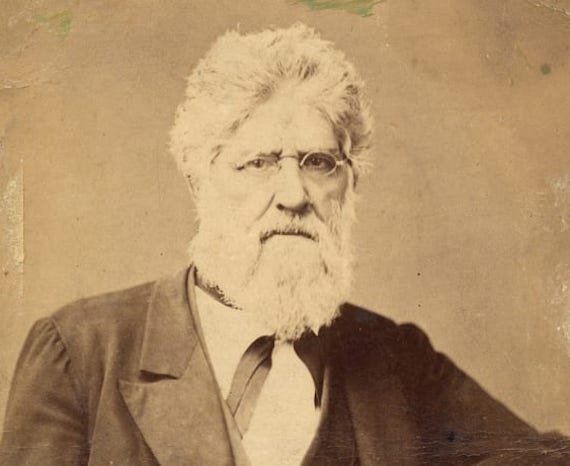

ANDREA DIMITRY 1775-1852

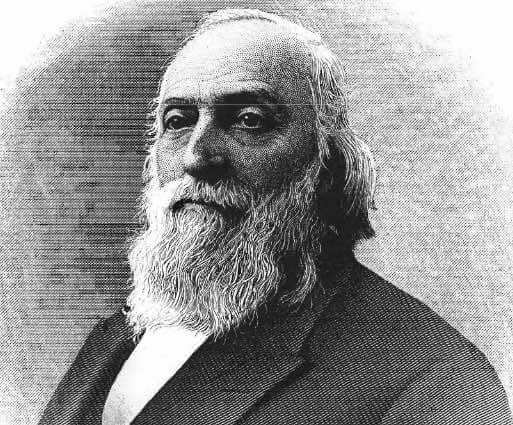

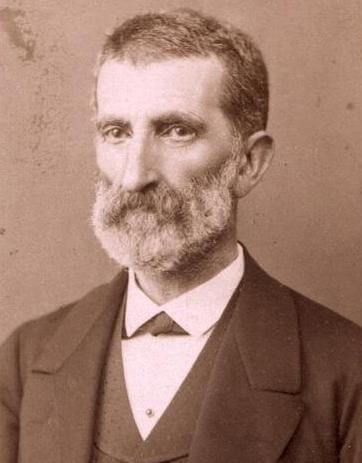

Andrea Dimitry (1775-1852)

A native of Greece, Andrea Dimitry was a veteran of the War of 1812 and the Battle of New Orleans. He was also a New Orleans shipping merchant.

First Greek Couple of North America: Andrea Dimitry and Marianne Celeste Dragon

The biography of Andrea Dimitry is given in the book "A Collection of Distinguished Southern families" by Louise De Bellet:

"Andrea Dimitry, a native of the island of Hydra, in the Grecian Archipelago, son of Nicholas Dimitry and Euphrosine Antonia, was known in his own country by the name of Andrea Drussakis Dimetrios Apolocorum. The family was one of the ancient Macedonian stock, one of those families that abandoned their pastoral homes and herds after the conquest of Macedonia by the Turks, and fled to the rock isles of the Archipelago. The family or tribe of Drussakis settled on the Island of Hydra, from which Andrea Dimitry landed in the spring of 1799 in New Orleans, La.

"Naturally, on arriving in a new country he sought among the residents those of the same language and country as himself, and among them he found Michael Dracos, a prosperous and wealthy merchant, to be the most prominent. Dracos was pleased to find in Dimitry a man of refinement and knowledge of the world, and requirements of trade, and also having the advantage of a good education. He therefore advanced his interests and gave him a seat at his table, and in October, 1799, he was married to the beautiful Marianne Celeste Dracos, daughter of his host. By her he had a large family, rose to wealth and prominence in the community and died March 1, 1852.

"'Andrea Dimitry took part in the war of 1812 to 1815, a:;sisting in the defense of New Orleans. The records of the War Department show that he was a private, in Captain Frio Delabostris' company (second Cavaliers), Louisiana Militia. He enlisted December 16, and served two years and twenty-five days."

The Times Delta of New Orleans carried this article on March 2, 1852, on the death of Andrea Dimitry:

"A noble veteran is gone. We have to record this morning the death of the venerable Andrea Dimitry, one of the oldest citizens, who was esteemed and beloved by a multitude of friends. Throughout his life he has been distinguished for a high sense of honor and for an integrity that brooked no thought of self. His social and domestic duties were performed with 0xemplary solicitude, and dying in his 80th year, he lived to see a posterity grow up about him, honored for their talents and their virtues. In his son, Alexander Dimitry, whom Louisiana proudly claims as her own, is reflected the purity of character and eminent virtues of his father."

Page 17

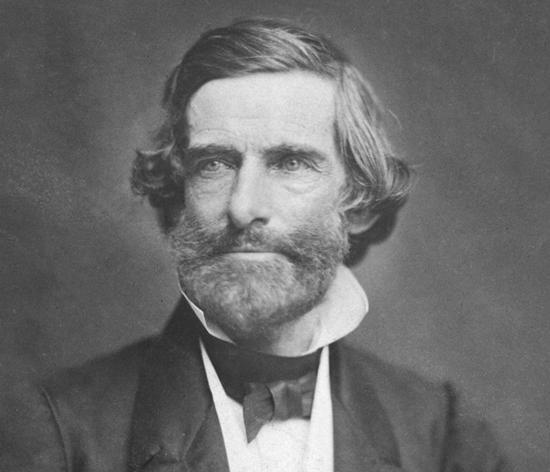

ALEXANDER DIMITRY (1805-1883)

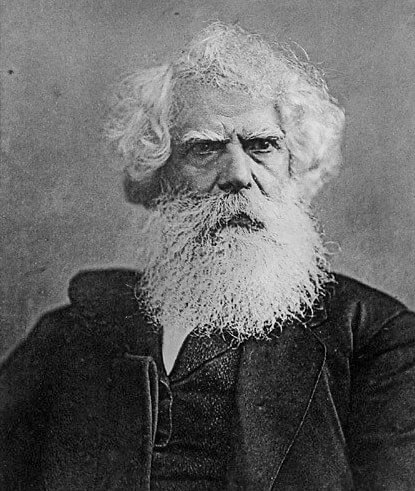

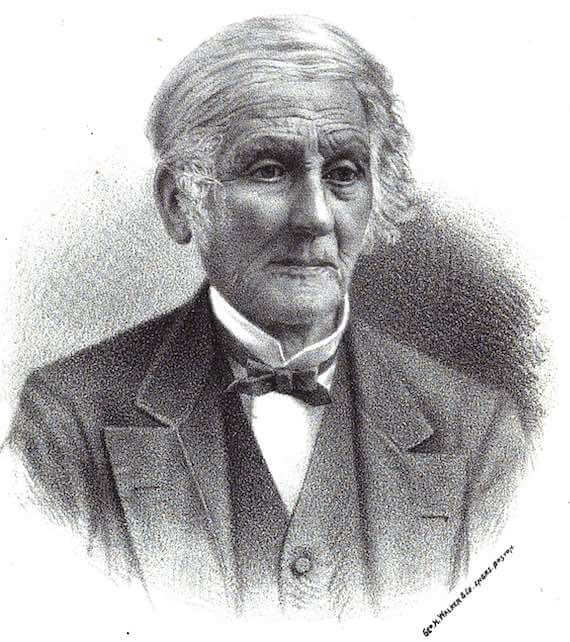

Alexander Dimitry

Alexander Dimitry (1805-1883) was the son of Andrea Dimitry (1775-1852) and Marie Celeste Dragon (1777-1856).

(Reprinted from The Times Democrat, New Orleans, January 31, 1883)

'"Prof. Alexander Dimitry was born in New Orleans on the 7th day of February, 1805, at No. 4 St. Anne St., opposite Jackson Square. The row of houses of which this house, the residence of his parents, was one, was demolished many years ago to make room for the present Pontalba Buildings. Mr. Dimitry's father, Andrea Dimitry, was a merchant of New Orleans for many years. He was a native of the Island of Hydra, in the Grecian Archipelago, and came to New Orleans during the last quarter of the last century.

"Professor Dimitry's maternal grandfather, Michael Dracos, was a native of Athens, Greece, and a member of an ancient family of that old center of civilization. He came to New Orleans a young man about 1766 and engaged in mercantile pursuits, becoming a merchant and importing his merchandise in his ship from the West Indies. He died in the year 1824 aged 82. His remains, together with those of his wife, Professor Dimitry's father and mother and many other members of the family, lie in the family tomb in the Old St. Louis Cemetery. His life size portrait in oil represents him as a man of stern features, of the pure Greek type and attired in the Spanish military uniform of nearly a century ago. Through his mother, the daughter of Michael Dracos, Professor Dimitry was descended from the aboriginal population of Louisiana. He was the fourth descendant from an Indian ancestress Miami of the nation of the Alibamous -- a nation long extinct -- who was born about 1690 in the land of those Indians, near the site of the Old French Fort St. Etiene, in what is now the State of Alabama.

"Professor Dimitry's parents, their means amply affording it, gave him every educational advantage and his intellect was no common one. Mr. Dimitry was sent to the school of Mr. Henry P. Nugent, a scholar and an Irish patriot of 1798. He remained there two years and when Rev. James J. Hull, an Episcopalian minister, opened his academy two years later he attended his school. Our venerable fellow citizens, General Lewis and Commander Huntes, were his classmates at Mr. Hull's Academy. At the age of 15 he was sent to Georgetown College in the District of Columbia. Here, after a brilliant course he graduated with the highest honors. He received his diploma at the commencement exercises in the presence of President John Quincy Adams, who in his remarks to the graduation class, especially commended him. Long after his day of graduation and when in fullness of his prime, Georgetown College conferred on her honored one the degree of LL. D.

"Returning to New Orleans, he studied law in conjunction with his friend, the late Christian Reselius. But he did not continue the practice of the profession. He accepted, by preference, being a devoted friend of education, a position as professor in the College of Baton Rouge. Here he stayed two years and it was from his incumbency of this professorship that he received the title of "Professor" by which he was so generally known. From the college he returned to this city to assist in editing the New Orleans Bee, having purchased a share in the paper, which was owned by Mr. Bayon and the late Mr. Delaup. The paper was at that time published entirely in French, but Mr. Dimitry gave its English side and became its first English editor. He was then 27 years of age. In the year 1835 Mr. Dimitry was married in the city of Washington to Mary Powell Mills, daughter of Robert Mills of South Carolina, for many years architect of the United States Government. He was the architect of the National Washington Monument, and of many of the great public edifices of the country at the National Capital and elsewhere.

Page 18

"In 1835 Mr. Dimitry was appointed by Postmaster General Kendall to an important clerkship in his department. In 1839 he served as Secretary of the United States Commission to arrange certain unsettled American-Mexican claims. In this position his marvelous knowledge of nearly all modern languages first drew attention to his power as a linguist. At the expiration of his work with the Commission he was offered the presidency of Franklin College in this state, which, however, he declined to establish a college of his own in St. Charles parish. He conducted this institute successfully for several years, and here many of the most prominent creole youths of that day received their education. He subsequently accepted the position of Superintendent of the Public Schools of the Third Municipality in this city, and later at the request of the joint committee of the General Assembly submitted a plan for a general system of public education throughout the state. The plan was accepted and Mr. Dimitry was appointed by the Governor the first State Superintendent of Louisiana.

"A state's rights Democrat in politics, Mr. Dimitry was in those days a foremost orator of the party in this city. Always a friend and advocate of the people in all honest demands the people returned his friendship fourfold. In recognition of his services as Stale Superintendent, the Legislature, on his retirement from office, voted him a testimonial. In 1854 Mr. Dimitry was called to Washington by his old friend Governor Marcy at that time Secretary of State, to accept an office in the State Department. Previous to accepting, however, he was appointed by President Pierce to an important post in connection with the new Echota Treaty which included the removal of the Creeks and Choctaws from their old homes. These duties having been finished he was given the charge of a Bureau of Translation in the Stale Department. He continued in his position from 1855 to 1859 and his accomplishment as a linguist met the utmost demands of the vast diplomatic correspondence of foreign governments with that of the United States.

"In 1859 President Buchanan, convinced of Mr. Dimitry's abilities as a diplomatic statesman and proficiency in international law, appointed him, upon the return of General Mirabeau B. Lamar, Minister Resident and Plenipotentiary ad hoc to Central America. This double mission included the republics of Nicaragua and Costa Rica. Mr. Dimitry took his family with him to San Jose the capital of Costa Rica and the seat of the legation. At a great banquet given him by the notables of the city shortly after his arrival, he astonished them and won the lasting esteem of the people by replying to a toast in the most eloquent Castilian and a fervent speech which recalled whatever was most honorable and worthv in Costa Rican history. He succeeded fully in the object of his mission to Costa Rica and doubtless would have obtained a like success in Nicaragua but for the secession of the Southern States of the Union.

"A devoted lover of his state, and her prompt and staunch champion at all times and in every place, he al once resigned as minister when Louisiana seceded. On his return to Washington Secretary Seward expressed to him his regret that he had resigned his mission as it was desired that he should remain, but Mr. Dimitry was anxious to cast his fortunes with his people and shortly after the Battle of Bull Run he managed to leave Washington without his departure being known, crossed the Potomac and repaired to Richmond.

Page 19

”Here he was appointed Chief of the Finance Bureau of the Post Office Department of the Confederate States. At the evacuation of Richmond he left the Confederate Capital in the train that contained Jefferson Davis and other officials, and was present at the general breakup that followed. After the war, Mr. Dimitry lived for a few months in Fordham near New York and subsequently in Brooklyn. In 1867 he returned to his native city, which he longed to see once more, here to end his days. Since that time with the exception of a stay of a few years at Pass Christian, where he conducted an Academy, he had lived in New Orleans enjoying the society of old friends. His last connection with education in his State was with the Hebrew Educational Society of which he was President.

"For the past year or two Mr. Dimitry had been measurably failing in body, but not in mind. His almost total loss of sight aided materially in the decline of his physical faculties. His once powerful and compact figure was seen rarely on the streets of late. But the vigor of his intellect and his strong will remained unimpaired up to within a few minutes preceding his death, which was the result of old age, rather than of actual sickness. At ten minutes past 2 o'clock yesterday morning, while those members of his immediate family who are now in the city were grouped around his bedside, he passed away as gently as if he had sunk into a dreamless and undisturbed sleep.

"Professor Dimitry's reputation as scholar extended to Europe among men who took cognizance of the workers in home intellect abroad. He never wrote a book from a fixed determination not to do so; but he often, in this city and elsewhere, lectured on classical and educational themes in vein of scholarship and with an eloquence that was all his own. In his younger days he wrote many pleasant tales, but these were written for annuals and gift books to oblige friends among the Northern publishers.

"Mr. Dimitry had been a close and daily student since his graduation. Surrounded by his library which at one time comprised 15,000 volumes in all languages and most of which he had imported from Europe, he pursued his studies and investigations into the arcana of knowledge with indefatigable zeal. That theme which he had most profoundly followed and in which he seemed most absorbed, was that of the history and developments of roots and words of Anglo-Saxon origin and of languages affiliated therewith. Had he prepared from his voluminous notes a work on the subject of the meaning and origin of proper names and localities of various lands, especially of those of the British Islands, it would have included within it the history of nearly every proper name in the English language." ·

Page 20

THE 1821 GREEK WAR OF INDEPENDENCE

On March 25, 1821, Greece opened its War for Independence against its Turkish oppressors, after almost 400 years under Turkish rule.

A brief insight into the Greek War for Independence of 1821 will be presented, as well as America's support and the effects of such support which resulted in the emigration of several Greek war orphans to America, who attained great prominence in their contributions to American life.

On May 29, 1453, Constantinople finally fell, and this date also marks the beginning of virtual slavery for Greece, for a period of nearly four hundred years.

Greek sailors of the myriad islands surrounding Greece had ample opportunities to fit themselves with ships, under Turkish rule, for the Turk needed this Greek commerce for himself. Because of the corsairs, or pirates, that roamed the sea at that time, it was necessary that the fishing and trading boats be armed with cannon. These small ships were a great aid to the Greeks in 1821.

Russian trading ships were allowed to come and go freely through the Bosporus or Hellespont, and through the Mediterranean without impediment or inspection on the part of the Turks. What Greek vessels sailed the sea had been required to carry the Turkish flag. However, the Greek sailors circumvented this obstacle by raising the Russian flag on their vessels, consequently escaping search and seizure. These Greek traders soon established great communities among the Russian cities on the Black Sea in Odessa and Tagani, and also in Trieste and Venice in what is now Italy. These Greek merchants grew influential and prosperous through the years, and by the day of the revolution, they had the wealth necessary to aid their mother country in her fight for freedom.

With the fall of Constantinople, the scholars in Greece immediately fled to the other parts of Europe, taking refuge in Holland, England and France. This left little source of learning for the people, for soon the schools themselves were closed for lack of teachers and because of Turkish pressure. For almost three hundred years, until 1700 and thereafter, Greece had few schools and learning was denied the people. Illiteracy was common, except for what learning the Church offered. Finally, in the 18th Century the prosperous Greek communitv of traders and merchants in Venice started its own small Greek school and Church. The Black Sea communities followed suit, and then the program was broadened to include schools in Athens, with aid from these outside communities. Schools were also established in Giannena, Levadia, Patmos, etc. The schools grew -- scholars came from them, and teachers went out from them, to teach in other cities. Among the teachers who carried on their work were Eugenios Voulgaris, Nikeforos Theotokis, Constantinos Economos, Vamvas, Georgios Gennathios, and others. These teachers not only taught their pupils the Greek language, but also taught the hope of freedom, someday, for Greece. They preached a greater and free Hellas for the future. Many of the school classes were held at night, in out of the way places, for the Turks constantly sought to do away with schools, and places of learning among the Greeks.

Page 21

During these centuries, the Turkish armies were making headway into Europe, and actually had besieged Vienna twice, only to be driven back into Hungary each time. They dominated Hungary for 150 years before being driven out of that land. The states of Venice and Turkey were constantly at war with each other because of their interests in Greece. Venice controlled many cities in Peleponnesus and also the Cyclades Islands, Crete, Cyprus, and other localities. Through Venetian and Russian aid the Greeks arose in revolt many times during the 17th and 18th Centuries, but each was suppressed. However, these occurred only in restricted areas and were not widespread. The results of these uprisings were great massacres by the Turks in the cities of Thessaly, in Crete, Smyrna and in central Greece as well.

The national secret society, which was international in scope, was the Philiki Etairia. This societv was formed bv three Greek merchants of Odessa, Skoufas, Tsakaloff, ·and Zanthos. The membership was secret for it meant death at the hands of the Turks to be known as a member of the society. Headquarters were established in Constantinople, and the movement officially opened for freedom for Greece. Alexander Ypsilanti, a general in the Russian army, was chosen the leader of the Philiki Etairia. (June, 1820).

Ypsilanti's first move was the organization of the revolution against the Turks in Moldavia and Vlachia (now Romania). Russian influence in that section was great, and the revolution was started there so as to influence the Turks into believing that the revolution was backed by Russia, and also to give the Greeks time in preparing for the movement in Greece, proper. However, the revolution in Moldavia failed and Ypsilanti was later taken by the Austrians, as he tried to flee through that country, and confined in prison. In 1827, the Czar of Russia intervened on his behalf and secured his release from prison, however, the confinement had undermined his health and he died within a year of his release.

In Constantinople, the news of the revolution caused great consternation among the Turkish officials. The sultan immediately ordered a move against all Greeks in that area, to stem any further uprisings. He ordered his troops to start wholesale pillaging and massacres against reputable Greek merchants and leaders. No one was spared, not even the venerable Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Constantinople, Gregory V.

On Easter Day, at the close of the services in the Greek Orthodox Churches, Turkish soldiers forced their way into the Greek Patriarchate in Constantinople, and showed papers to the Patriarch, which stated that he had been evicted from his post as Patriarch by the sultan. The soldiers then put the Patriarch in prison, where he remained for some time. The Patriarchate was given orders by the sultan, on pain of death, to select another Patriarch.

Finally, the Patriarch was taken from his prison, to the Patriarchate, and there hanged from the Inner Gate. His body was left there for three days, while all Christians hid in their homes for fear of their lives, as the Turkish soldiers roamed the city, searching for Greek Christians. Those that they found, were slaughtered. Then, the body of the Patriarch was taken down, weighted with a heavy stone, and thrown into the sea, by the Turks. However, a Greek ship captain, several days later, sighted the floating body, which had come to the surface, brought it aboard his ship upon recognition, and carried it immediately to Odessa in Russia. There, the Czar gave the Patriarch the honor due him, with a state funeral, and great mourning. After fifty years, the body was exhumed and taken to Athens, where it lies today.

Page 22

This action, and others, on the part of the Turks, were made in order to suppress any movement towards revolution, however, they only served to add more fuel to the flame of revolt.

In 1821, through the efforts of the Philiki Hetairia, the secret society and under the leadership of such men as Theodore Kolokotronis, Petrompes Mavromichalis, Andreas Zaimis, Andreas Lontos, the Metropolites Palaion Patron Germanos, Gregorios Papaflesas -- the revolution opened in Greece. Kolokotronis arrived at Mani, in January of 1821, and his very presence in Greece was enough to arouse the spirit of the patriots, for his name was already knownthroughout the country, as a fearless patriot, and leader. In 1818, the Turks had evicted him from the Morea, or Peleponnesus, because of his aggressiveness and rebellious spirit.

On March 21, 1821, the patriots besieged the city of Kalavrita, and in five days had taken the town. On the 22nd, Mavromichalis and his Maniates, with Kolokotronis and others, besieged Kalames and took it on the 25th. In Patras, the Metropolites Palaion Patron Germanos, with Andreas Zaimis, Lontos and others, struck the colors for freedom, on March 25, which date is recognized as the official beginning of the Revolution. With their force, these leaders besieged the town of Patras. At the same time, Lala, Corinth, Monemvasia, Navarino, Argos, and Nauplion were besieged by the patriots. The Greek patriots finally took Navarino, Monemvasia, and Corinth, in 1822.

The revolution was raised in sterea Hellas by Panourgias at Amphissa, by Thanasis Diakos at Levadia, and by Diovouniotis at Voudounitsa. The revolution opened on May 20 in northern Greece. Because of the heavy Turkish forces in that section, the struggle did not meet with any success. In Thessaly, the uprising was quickly downed by the Turks who massacred and destroyed as they went through the countryside. In Macedonia, the heavy Turkish forces spelled defeat for the Greeks there, also. In Crete the Greeks arose in revolution, but had to flee to the hills for safety where they remained for the duration of the struggle, fighting for their lives against the Turks. In the islands, lay the greatest wealth of Greece, because of trading and commerce which they carried on. The islands joined with the rest of the country in the revolt, and on April 3, the Spetses Isles revolted, sending 58 ships to besiege Nauplio from the sea. Hydra, Psara, and Spetses bore the brunt of the revolution among the islands, since they led them in importance. Shortly after, Samos, the Cyclades, and the Dodecanesa, except for Rhodes, also joined in with the revolutionists.

Page 23

The First Government

The first government of the revolutionary forces was formed at Epidaurus. A committee was selected to rule, with Alexandros Mavrokordatos as the president, and leader. From this seat, the revolution was directed, and the forms of attack were planned. However, shortly thereafter, at Peta, the Greeks suffered their first great loss, losing 3,500 men, being routed from the field, to Missolonghi, where the survivors took refuge while the Turkish forces besieged the city. The siege lasted for years, resulting in hardships and suffering for those in the city. It was here at Missolonghi that Marco Bozzaris first sprang into fame for his bravery and leadership. A Turkish surprise attack on Christmas Eve against the city, intended to catch the Greeks while attending church services, was frustrated when news of the attack became known, and the patriots were in readiness for it. The Turks were routed completely, and the patriots pursued them as far as the Achelo River, where over 500 of the enemy drowned in its icy waters, trying to ford it. At Peta, a large detachment of Philhellenes from all parts of Europe, formed together to aid the patriots, suffered almost complete annihilation. The rest of the world was already giving some response to Greece's need, although the great drive for aid and relief had not yet begun in earnest.

During these dark days it was Kolokotronis who saved Greece from being taken again by the superior forces of the Turks, for time and again, through his strategy and leadership, he constantly harried the enemy, keeping them at bay, and worrying them, keeping them disorganized. Kolokotronis asked the other Greek leaders to follow his plan, for he realized that the Turks would march towards Corinth, instead of retreating as the other leaders insisted. They scoffed at him, but he took up his position in the hills, and when the Turks did appear, on the way to Corinth, he was the actual savior of Greece, for he engaged them with his small force, until aid came from the other leaders.

European Philhellenism

When news of the Greek Revolution spread throughout Europe, the great scholars on the continent began the campaign for aid to Greece, which led, ultimatelv, to financial and material aid in soldiers and ships. In Switzerland, France, and Germany societies were formed to aid the patriots. The government of England was not in favor of the revolution at first, however after constant pressure from internal groups, she was forced to accede to the demands of the English, and favor swung towards aid for Greece. It was Lord Byron who raised his voice and power to bring material and financial aid to Greece, and he went so far as to expend his own personal fortune in aiding the patriots, and died in Greece, at Missolonghi, during the siege, of fever.

Page 24

In America, Samuel Gridley Howe, and others, gave aid to Greece. Funds were raised and sent over, with shiploads of supplies. Men volunteered to fight for the Greeks.

The Turks realized that, alone, they could not overthrow the Revolution, and they called upon the Egyptians to aid them. They quickly received an enthusiastic response, and large forces of Egyptians began arriving in Greece. Immediately there followed the massacres of Crete and of Kaso. Men, older folk and children were massacred, and more than 2,000 young girls were taken to the Alexandrian slave markets to be sold as slaves. It was another example of Turkish warfare that horrified Europe.

In 1824, 176 Turkish ships sailed against Psara, which had only 3,000 soldiers, but over 30,000 women and children and old men under their protection, who had come there from the various other islands, after Turkish massacres. The thousands of Turkish soldiers landed, and soon swept the island clear of human life, for more than three-quarters of the population was massacred.

Aid from the European Powers

In 1827 when the revolution seemed doomed to failure, the European powers entered the picture. England, France, Russia and Austria had previously lent no governmental aid to Greece, nor sanctioned the revolt, because of fear of international complications. However, with the advent of Nicholas as Czar of Russia, and of Canning as prime minister of England, the scene changed for the better, for the patriots. France, England, and Russia met in London in 1827 and signed a secret treaty, agreeing to support the revolutionary government of Greece, and to rid Europe of Turkey. They also saw a sphere of influence in the Balkans that they had not molested heretofore, which had suddenly gained a great importance.

England, France and Russia immediately sent their fleets to Greek waters, and ordered the Egyptian and Turkish commanders to take their troops and their ships and vacate the Peleponnesus and its waters. The Turks refused, upon further orders from Constantinople. In the meantime, the Greek forces had taken new heart upon the good news, and the revolution sprang up anew. Ibrahim then began anew to scourge the Peleponnesus sweeping through Messenia, Arcadia and Laconia. Following this action, the French, Russian and English ships swept into Navarino and gave final orders for the Turkish-Egyptian fleets to leave the waters of the country at once. The Turkish fired and sank a small English boat. Following this action, Codrington, the English commander, gave orders to start firing. Within four hours, only 20 of the original 120 Turkish-Egyptian ships remained afloat on the water. All the rest had been sunk.

Page 25

This destroyed Turkev's power in Greece forever. French soldiers were then landed in the Peleponnesus, and Ibrahim was forced to flee the country with his Egyptians, back to Egypt. Finally, on September 12, 1829, all of central Greece and the Peleponnesus had been cleared of Turkish forces.

Prince Othon of Bavaria, son of Ludovici, King of Bavaria, only seventeen years of age, assumed the crown as King of Greece on Januarv 25, 1832, and peace reigned in the land for the first time in almost four hundred years. The people welcomed him as a savior for now they were united, as a recognized nation of the world. And freedom came to Hellas, again.

American Aid to Greece

On May 25, 1821, Petros Mavromichalis, Director General of the Messenian Congress at Kalamata, wrote a letter addressed to the people of the United States, in which he asked for America's help.

This letter was translated into both English and French, and reached the attention of American Ambassador to France Albert Gallatin, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, and Dr. Edward Everett of Harvard University. A letter to Everett was also sent from Paris, and Adamantios Koraes was one of the signers, asking for assistance from America. Dr. Everett published these letters in his North American Review, and through his personal efforts, the Greek War of Independence received wide publicity in America, resulting in widespread support from the American people.

Adamantios Koraes wrote to Thomas Jefferson, from Paris, on July 10, 1823, asking for America's help, and support, and Jefferson replied with fervent hope for Greece's success, and his support, and with suggestions. In addition, there was correspondence from Lafayette to Jefferson urging American recognition of the Greek stand for independence.

Many Americans also urged Congress to immediately recognize the Greek stand for independence, but there was hesitancy on the part of Congress to interfere in European matters at the time.

However, public support among Americans became so strong that there were Greek Committees established in many cities, and private contributions were given for the aid of the Greeks with food, clothing, and medicine.

On March 5, 1827 the ship Chancellor left from New York with escort Jonathan P. Miller, with supplies worth $17,500. Miller had previously been in Greece, returned to the C.S., to raise supplies, and was now returning to Greece again.

On May 12, 1827, the ship Six Brothers left for Greece with a cargo of supplies worth $16,614, with escort John R. Stuyvesant.

The ship Jane left New York on Sept. 14, 1827, with $8,900 worth of supplies for Greece, with escort Henry A. V. Post. Post later published a book of his experiences.

Page 26

From Philadelphia, two ships, the Levant and the Tontine, departed for Greece with $13,856.40 and $8,547.18 in supplies. J. R. Leib accompanied the ships as escort for the supplies.

In the spring of 1827, the ship Statesman departed from Boston with $11,555.50 in supplies, with John B. Russ as escort.

Boston, New York, Philadelphia and other cities created Greek Relief Funds, and contributions poured in. The money raised was used to buy supplies which were sent to the starving, ill-clothed, ille-quipped army and people of Greece. Instances of specific contributions are: the undergraduate students of Yale Lniversity gave $500; the Theological School at Andover College in Massachusetts collected money for the Fund, as did Columbia University students in New York. Young people's groups in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and Albany, :'Ii. Y., gathered money. Two churches in Boston gave S300 each. On January 8, 1824, a large ball was held in New York City for which tickets sold for $5.00 each. Over 2,000 persons attended the affair, netting $10,000 for Greece. By the end of April, 1824, New York City philhellenes had contributed over $32,000.

Influential American families adopted Greek orphans brought from Greece, and many of these attained high rank in American political and professional life.

Although we hope to briefly recount the story of the American Philhellenes who assisted Greece during her War of Independence, tribute must first be paid to the great English poet Lord Byron, who called the attention of the world to Greece's desperate struggle for freedom and existence.

Lord Byron arrived at Missolonghi on December 24, 1823, where he was warmly welcomed by the Hellenes. He delighted in wearing the Greek foustanella. With his own money, he supported 500 Souliotes soldiers, and gave greatly of his own wealth for the cause of Greece. However, illness struck on April 6, 1824, and on April 7, 1824, he died, at 37 years of age, with these words on his lips:

"Greece, I gave you everything that any one man can give. I gave you my wealth -- my health, and now -- my very life. My sacrifice is for your salvation."

Monuments now stand to his memory in Missolonghi, and also at the Zappeion in Athens.

Because of the bitter defense, and the deeds of heroism and valor displayed at Missolonghi during the four years of siege by the Turks (1822-1826), the city has become the "Shrine" of the 1821 Greek War of Independence. There, all nations whose Philhellenes aided Greece in its cause, have monuments to the memory of those brave men from other countries who died at Missolonghi and in other battles of the revolution.

These monuments include a memorial erected by the Order of Sons of Pericles, the Junior Order of Ahepa, in 1939, and placed there in memory of the American Philhellenes.

Page 27

PRESIDENT JAMES MONROE

On December 3, 1822, President James Monroe included the following words in his Message to Congress:

"The mention of Greece fills the mind with the most exalted sentiments, and arouses in our bosoms the best feelings of which our nature is susceptible. Superior skill and refinement in the arts, heroic gallantry in action, disinterested patriotism, enthusiastic zeal and devotion in favor of public liberty, are associated with our recollections of ancient Greece. That such a country should have been overwhelmed, and so long hidden as it were, from the world, under a gloomy despotism, has been a cause of unceasing and deep regret to generous minds for ages past. It was natural, therefore, that the reappearance of these people in their original character, contending in favor of their liberties should produce the great excitement and sympathy in their favor, which have been so signally displayed throughout the United States. A strong hope is entertained that these people will recover their independence, and resume their equal station among the nations of the earth."

DANIEL WEBSTER OF MASSACHUSETTS

U.S. Representative Daniel Webster of Massachusetts introduced a Resolution in the House of Representatives during the 1823-1824 Congressional 18th Session:

"That provision ought to be made, by law, for defraying the expense incident to the appointment of an agent, or commissioner, to Greece, whenever the President shall deem it expedient to make such an appointment.

"This people, a people of intelligence, ingenuity, refinement, spirit, and enterprise, have been for centuries under the most atrocious, unparalleled Tartarian barbarism that ever oppressed the human race. This House is unable to estime duly, it is unable even to conceive or comprehend it. It must be remembered that the character of the forces which has so long domineered over them is purely military. It has been as truly, as beautifully said, that "The Turk has now been encamped in Europe for four centuries. Yes, sir -- it is nothing else than an encampment. They came in by the sword, and they govern by the sword …

"Sir, while we sit here deliberating, her destiny may be decided … . They look to us as the great Republic of the earth -- and they ask us by our common faith, whether we can forget that they are now struggling for what we can now so ably enjoy? I cannot say, sir, that they will succeed; that rests with heaven. But for myself sir, if we tomorrow hear that they have failed -- that their last phalanx had sunk in its ashes and that naught remained but the wide melancholy waste where Greece once was, I should still reflect with the most heartfelt satisfaction, that I had asked you, in the name of seven millions of freemen, that you would give them at least a cheering of one friendly voice."

Page 28

HENRY CLAY OF KENTUCKY

U.S. Representative Henry Clay of Kentucky spoke in the same Session of Congress in support of the Resolution introduced by Daniel Webster, as follows:

"The question has been argued as if the Greeks were likely to be exposed to increased sufferings in consequence of such measure; as if the Turkish scimetar would be sharpened by its influence, and dyed deeper and yet deeper in Christian blood. If such is to be the effect on the declaration of our sympathy, it must have happened already. That explanation is very fully and distinctly given in the message of the President to both Houses of Congress, not only this year, but last."

JOHN QUINCY ADAMS

(President of the United States. Annual message, December 4, 1827)

"The sympathies which the people and Government of the United States have so warmly indulged with the cause of Greece have been acknowledged by their government in a letter of thanks, which I have received from their illustrious President, a translation of which is now communicated to Congress. We hope that they will obtain relief from the most unequal of conflicts which they have so long and so gallantly sustained; that they will enjoy the blessing of self-government, which by their sufferings in the cause of liberty they have richly earned, and that their independence will be secured by those liberal institutions of which their country furnished the earliest examples in the history of mankind, and which have consecrated to immortal remembrance the very soil for which they are now again profusely pouring forth their blood."

THOMAS L. WINTHROP and EDWARD EVERETT

From an address of the Committee appointed in a public meeting held in Boston, December 19, 1823, for the relief of the Greeks:

"We call upon the friends of freedom and humanity to take an interest in the struggles of five millions of Christians rising not in consequence of revolutionary intrigues as has been falsely asserted by the crowned arbiters of Europe, hut by the impulse of nature, and in vindication of rights long and intolerably trampled on. We invoke the ministers of religion to take up a solemn testimony in the cause; to assert the rights of fellowmen, and of fellow-Christians; to plead for the victims whose great crime is Christianity. We call on the citizens of America to remember the time, and it is within the memory of thousands that now live, when our own beloved, prosperous Country waited at the door of the court of France and the States of Holland, pleading for a little money and a few troops; and not to disregard the call of those who are struggling against a tyranny infinitely more galling than that which our fathers thought it beyond the power of man to support. Every other civilized nation has set up this example; let not the freest state on earth any longer be the only one which has done nothing to aid a gallant people struggling for freedom."

Page 29

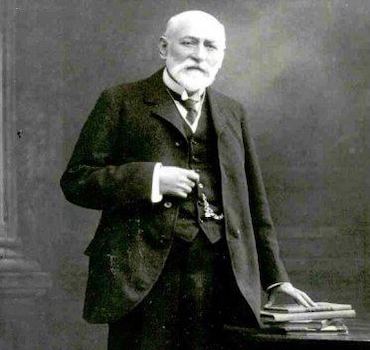

DR. SAMUEL GRIDLEY HOWE

Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe

Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe, who completed his medical studies at Harvard University in 1824, departed that same year for Greece, to observe the struggle for independence and to assist the Greeks. He was horn in Boston, November 10, 1801; graduated from Brown University in 1821; received his medical degree from Harvard.

He was the author of a book, "An Historical Sketch of the Greek Revolution" which was published upon his return to America, and which received wide readership. The Howe book has been reprinted by Dr. George C. Arnakis of the Center for Neo-Hellenic Studies, of Austin, Texas.

Dr. Howe stayed in Greece from his arrival at the close of the year 1824, until November 13, 1827, when he departed for the United States. On November 12, 1828, he arrived back in Greece at Aegina, and stayed until June of 1830, when he returned to America to continue his professional career as a doctor.

While in America between the trips to Greece, he spent almost all of his time campaigning for Greek Relief, lecturing in behalf of the many Greek Committees in the United States, and working on his book for publication.

During his first years in Greece he was a surgeon in the Greek armed forces and was given the title of "Surgeon-in-Chief" by the Greek government. Dr. Howe also took part in several engagements, wore the foustanella on some occasions, and gave invaluable service to the Greek forces.

On his second trip to Greece he escorted a large supply of American materials, which he distributed to the Greek war refugees, with the assistance of Jonathan P. Miller and George Jarvis.

Dr. Howe again visited Greece in 1844 for a brief time, and in 1867 he returned to Greece with his family, at a time when the Cretans were fighting for freedom from Turkey.

Page 30

LETTER TO AHEPA FROM HOWE'S DAUGHTER

In the early part of the year 1932, Mrs. Maud Howe Elliott of Newport, R.I., sent the following letter to the Order of AHEPA, about her father, Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe:

"Dear friends of the AHEPA, I send you my loving greetings and only wish I could give them in person at this meeting commemorative of the first centenary of Greek Independence. Looking back these hundred and more years I seem to see the face of my father, a young man of twenty-three years of age, who in the year 1824, just at the beginning of his career, after having been graduated from Brown University and Harvard medical school, turned away from the beaten path of his profession, and alone and against the advice of his parents and his friends, embarked on a small sailing vessel for the Mediterranean, landing near Navarino and reaching Tripolitza in the winter of 1824-25.

"In his first letter home he writes to his friend, William Sampson:

"I hope to reach Greece before the first of January. If I succeed in getting a commission in their army or navy, I shall remain in the country for some years, perhaps for my life."

"In March, 1825, he writes to his father:

"First of all I am sincerely glad I have come to Greece. My commission as army surgeon is filled out. As for my salary, I have nothing and care nothing about it; the government is not able to feed and clothe their poor suffering soldiers, and I have not the heart to demand money. I have clothes enough to last a year and at the end of that time, if not before, I shall probably put on the Greek dress."

"He did put it on, and in memory of his wearing of the uniform you all know as that of the evzones, my husband, John Elliott the artist, made several portraits of him, one of which is in Brown University, another in the Ethnological Museum in Athens.